Notas Técnicas de ECHO (TN)

Notas Técnicas de ECHO son publicaciones que tratan específicamente a un tema importante para aquellos que trabajan en los trópicos y subtrópicos. Nuestro material es escrito por funcionarios de ECHO y escritores ajenos, los cuales tienen experiencia y conocimientos con la técnica. Estos documentos están disponibles de forma gratuita y ¡esperamos que sean valerosos para su biblioteca de recursos en el desarrollo de agricultura!

100 Contenido (Mostrando Ediciones 43 - 34) Anterior | Próximo

Filtro de Agua Bioarena - 1/1/2001

- También disponible en:

- Français (fr)

- English (en)

Los servicios inadecuados de agua potable y saneamiento resultan en un estimado de 4 mil millones de casos de

diarrea y 2.2 millones de muertes cada año (OMS/UNICEF 2000). En áreas donde no hay acceso a agua potable,

el tratamiento del agua en los hogares puede contribuir de manera significativa a reducir los problemas de salud

relacionados con el agua. Los métodos de tratamiento del agua más efectivos siguen un proceso de sedimentación,

filtración, y desinfección para eliminar bacterias, virus, helmintos y protozoarios.

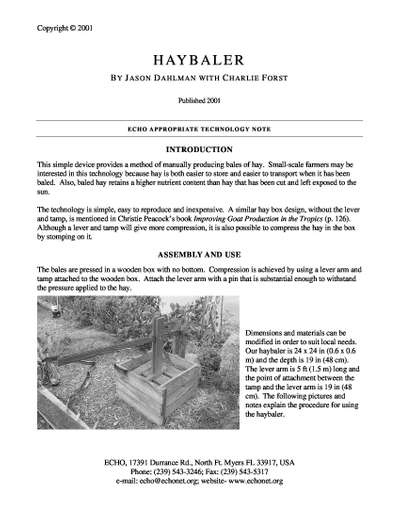

Haybaler - 1/1/2001

This simple device provides a method of manually producing bales of hay. Small-scale farmers may be interested in this technology because hay is both easier to store and easier to transport when it has been baled. Also, baled hay retains a higher nutrient content than hay that has been cut and left exposed to the sun.

Solar Dehydrator - 1/1/2001

Often the biggest challenge faced by a tropical farmer is not in the production of a crop but rather in the preservation of the crop. Farmers may want to preserve a crop for future consumption or for sale at a time when the market will offer a higher price.

Using a solar dehydrator is a simple, cost-effective way to preserve a variety of different crops. Dehydrating removes the moisture from food so that bacteria, yeast and mold cannot grow and spoil it.

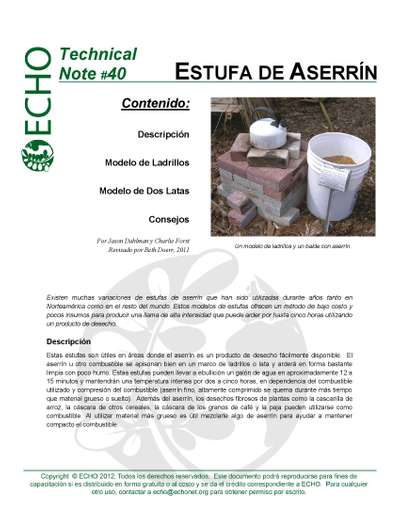

Estufa de Aserrin - 1/1/2001

- También disponible en:

- Français (fr)

- English (en)

Estas estufas son útiles en áreas donde el aserrín es un producto de desecho fácilmente disponible. El aserrín u otro combustible se apisonan bien en un marco de ladrillos o lata y arderá en forma bastante limpia con poco humo. Estas estufas pueden llevar a ebullición un galón de agua en aproximadamente 12 a 15 minutos y mantendrán una temperatura intensa por dos a cinco horas, en dependencia del combustible utilizado y compresión del combustible (aserrín fino, altamente comprimido se quema durante más tiempo que material grueso o suelto). Además del aserrín, los desechos fibrosos de plantas como la cascarilla de arroz, la cáscara de otros cereales, la cáscara de los granos de café y la paja pueden utilizarse como combustible. Al utilizar material más grueso es útil mezclarle algo de aserrín para ayudar a mantener compacto el combustible.

Temas Relativos a la Introduccion de Nuevas Semillas en el Extranjero - 21/1/2000

- También disponible en:

- English (en)

- Français (fr)

Usualmente los norteamericanos no tienen idea de cuan diferente puede ser la horticultura en el trópico. Personalmente experimenté algo de este fenómeno cuando me mudé de Ohio en 1981 para convertirme en Director de ECHO. Yo ya había comprado semillas para mi jardín en Ohio cuando surgió la oportunidad de trabajar con ECHO. De manera que a finales de junio comencé a sembrar en mi huerto en el sur de la Florida. Me quedé perplejo cuando un señor de edad me dijo, “Aquí en Florida no cultivamos hortalizas en verano. Simplemente las dejamos crecer como maleza y no las tocamos hasta el otoño." -- ¿Porque alguien haría algo así?

Cashew - 1/1/1999

The cashew, Anacardium occidentale, is a resilient and fast-growing evergreen tree that can grow to a height of 20 m (60 ft). It belongs to the family Anacardiaceae, which also contains poison ivy and the mango. Native to arid northeastern Brazil, the cashew was taken around the world by the Portuguese and Spanish who planted the trees in their colonies. The English name "cashew" is derived from the Portuguese "cajú" which came from the Tupi Indian "acaju" (Rosengarten, 1984). In Spanish it is known as "marañón" or "anacardo."

Cashew is an important nut crop that provides food, employment and hard currency to many in developing nations. Of all nuts, cashew is second only to the almond in commercial importance (Rosengarten, 1984). India, Mozambique, and Tanzania are the three biggest exporters of cashew nuts today. Although there are large commercial plantings of cashew, wild trees or those owned by small farmers account for 97% of cashew production (Rosengarten, 1984).

The plant produces not only the well-known nut, but also a pseudofruit known as the cashew "apple" and cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) which is used for industrial and medicinal purposes.

The cashew tree has other uses as well. It is used for reforestation, in preventing desertification and as a roadside buffer tree. Cashew was planted in India in order to prevent erosion on the coast (Morton, 1960). The wood from the tree is used for carpentry, firewood, and charcoal. The tree exudes a gum called cashawa that can be used in varnishes or in place of gum arabic. Cashew bark is about 9% tannin, which is used in tanning leather.

Egusi Recipes - 1/11/1998

In West Africa, the name Egusi is applied to members of the gourd family having seeds of high oil content. Egusi Melon plants closely resemble watermelon plants; both have a non climbing creeping habit and deeply cut lobed leaves. The pulp of the watermelon fruit, however, is sweet and edible while the Egusi Melon has bitter and inedible fruit pulp. Egusi Melon seeds are larger than watermelon seeds, and they are light colored. Egusi Melon is cultivated in portions of West Africa, especially in Western Nigeria, for the food in the seed and as a crop interplanted with maize, cassava, or other crops.

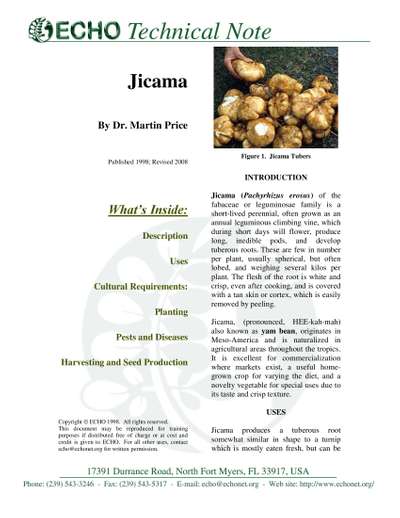

Jicama - 1/10/1998

- También disponible en:

- Français (fr)

- English (en)

Jicama (Pachyrhizus erosus) of the fabaceae or leguminosae family is a short-lived perennial, often grown as an annual leguminous climbing vine, which during short days will flower, produce long, inedible pods, and develop tuberous roots. These are few in number per plant, usually spherical, but often lobed, and weighing several kilos per plant. The flesh of the root is white and crisp, even after cooking, and is covered with a tan skin or cortex, which is easily removed by peeling.

Jicama, (pronounced, HEE-kah-mah) also known as yam bean, originates in Meso-America and is naturalized in agricultural areas throughout the tropics. It is excellent for commercialization where markets exist, a useful home-grown crop for varying the diet, and a novelty vegetable for special uses due to its taste and crisp texture.

Quail: An Egg & Meat Production System - 1/9/1998

Many families in the tropics must assume a major role in production of their own foodstuffs. Incomes are so low that purchase of food competes with purchase of necessary items that cannot be hand-made. Most governments in the tropics do not have the resources to guarantee even minimum food to all of their citizens. Families in rural and urban situations often live in a minimum of space without soil that can be cultivated, or even a backyard in which a few animal cages can be placed. Such persons sorely need small scale systems that are in harmony with resources available.

Unfortunately, not enough study has been given to small-scale production systems. The small animals typically encountered on almost every small farm, chickens, ducks, geese, and rabbits, are still too large for many households. A small animal for a minimum sized system should produce food in units that can be eaten at one meal so that refrigeration is not necessary. Furthermore, such systems should use resources available to most families, including feeds that can be grown or purchased, cages that are home made, and systems of sanitation that

protect the health of the animals and the residents of the household. The development of such systems has not attracted serious investigators.

The system described here, based on the Japanese quail, Coturnix japonica, is based on sound published information on this species and its requirements, and on three years of experimentation with quail at the household level. All apparatuses described were built and used, and actual costs and yields are reported.

Banana, Coco & Árbol de Pan - 1/6/1998

- También disponible en:

- English (en)

Hay más de cien especies principales de frutas en los trópicos, haciendo una contribución interesante al apetito y también a la nutrición. Estas especies varían en sus requerimientos ecológicos, en estación de producción, en rendimientos, usos, y por supuesto en otras características. Las tres frutas que son tratadas aquí son frutas sobresalientes por su importancia en alimentar a la gente. Estas frutas también producen mucha comida con un mínimo de esfuerzo. De hecho, forman parte de la dieta principal en los trópicos. En contraste, los mangos son muy importantes en los trópicos, pero pocas veces forman parte de la dieta principal. Los cítricos son variados, producidos ampliamente y disfrutados, pero nunca forman una parte principal de la dieta. Estos comentarios se pueden extender a otras frutas también.

Probablemente la fruta más importante de los trópicos en términos de distribución, uso y contribución como alimento es la banana (para fines de esta discusión, las bananas y los plátanos se considerarán juntos). Las muchas formas de comer estas frutas les hace un alimento diario muy popular. Su contribución nutricional primaria son sus calorías (en forma de almidón y azúcar).

El coco es común y es un alimento diario en algunas partes (pero no todas) de los trópicos. Se adapta bien y se puede cultivar en casi cualquier lugar. El árbol mismo es versátil en su aplicación y puede ser el árbol más útil de los trópicos. La fruta se usa en cada etapa de maneras únicas, y es una fuente significante de proteínas y una fuente principal de grasa en la dieta.

El árbol de pan, con nombre apropiado, sostiene la vida en el Pacifico. Su naturaleza como alimento principal es la razón para su introducción amplia en los trópicos. Para su tratamiento normal se han desarrollado métodos primitivos y modernos, y los cocineros nativos encuentran usos diversos para la fruta. Su contribución a la dieta es principalmente almidón, y las frutas maduras tienen altas cantidades de azúcar también.

Estas tres especies se pueden cultivar en el mismo terreno en áreas amplias de los trópicos. Una vez rinden, requieren de poco cuidado y rinden bastante para el esfuerzo requerido para producirlas.