ECHO Technical Notes

ECHO Tech Notes are subject-specific publications about topics important to those working in the tropics and subtropics. Our material is authored by ECHO staff and outside writers, all with experience and knowledge of their subject. These documents are free for your use and will hopefully serve a valuable role in your working library of resources in agricultural development!

101 Các Số trong Ấn phẩm này (Hiển thị vấn đề 84 - 75) Trước | Tiếp theo

Understanding Salt-Affected Soils - 17-08-2016

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- Français (fr)

- Español (es)

- English (en)

Farmers and gardeners in semi-arid and arid regions of the world face two associated but separate problems, which limit the crops they can grow and the yield of these crops. The underlying problem is lack of rainfall needed for growing plants. The second is accumulation of salts in the root zone. The two are interrelated, but do not necessarily occur together.

Plants need a certain amount of soluble salts, but excess salts in the root zone reduces plant growth by altering water uptake. When the salt content of soil water is greater than that of the water inside the plant cells, the plant roots cannot absorb the soil water. They may even lose water to the soil. Excess soil salts can also cause ion-specific toxicities or imbalances. In some cases, the cure for these problems is to simply improve drainage. However, salinity problems are often more complex and require proper soil management as well as use of salt tolerant crops.

What’s Inside:

- Introduction

- Formation of salt-affected soils

- Soil remediation

- Soil management

- Plant management

- Measuring soil salinity

Agriculture Extension with Community-Level Workers: Lessons and Practices from Community Health and Community Animal Health Programs - 04-11-2015

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- English (en)

- Español (es)

Active learning and exchange of knowledge are key to farmer adoption of beneficial agricultural innovations. Community health worker (CHW) and community animal health worker (CAHW) programs have led to a rich body of knowledge about extension, much of which is applicable to efforts aimed towards small-scale farmers. Drawn from the literature on these programs, this document captures key lessons and practices relevant to developing, implementing, and sustaining effective community agriculture extension endeavors. The objective of this paper is to inform and strengthen agricultural extension programs that provide services through community-level workers.

SRI, the System of Rice Intensification: Less Can be More - 21-09-2015

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- Français (fr)

- English (en)

- Español (es)

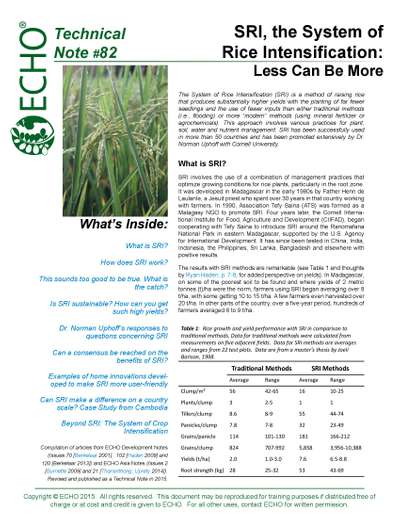

The System of Rice Intensification (SRI) is a method of raising rice that produces substantially higher yields with the planting of far fewer seedlings and the use of fewer inputs than either traditional methods (i.e., flooding) or more “modern” methods (using mineral fertilizer or agrochemicals). This approach involves various practices for plant, soil, water and nutrient management. SRI has been successfully used in more than 50 countries and has been promoted extensively by Dr. Norman Uphoff with Cornell University.

Introduction to Tropical Root Crops - 16-02-2015

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- Français (fr)

- English (en)

- Español (es)

Tropical root and tuber crops are consumed as staples in parts of the tropics and should be considered for their potential to produce impressive yields in small spaces. They provide valuable options for producing food under challenging growing conditions. Cassava and taro, for instance, are excellent choices for drought-prone or swampy areas, respectively. In this document, tropical root crops are compared both to enable people to recognize and appreciate them as well as to familiarize readers with their strengths and weaknesses in different tropical environments. Though tropical root crops initially seem to be very similar in their uses, they exhibit important differences.

Seed Fairs: Fostering Local Seed Exchange to Support Regional Biodiversity - 01-06-2014

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- Español (es)

- English (en)

When you come across an especially promising local variety of a crop grown in your area, how can you enable other farmers to try out this variety? If a farmer gives you 30 seeds of an exceptional variety, how might you go about distributing these? How does seed flow happen in and among communities where you work?

In this article, we share about ECHO Asia’s experience helping host four very different seed fairs. We also outline several important components of a seed fair, so you can learn from our experience if your organization is interested in hosting one.

An important activity of many ECHO network partners is supporting farmers in locating, testing, and distributing plant varieties that grow well under local conditions. Crops and varieties that can produce reliably with locally accessible inputs are essential for smallholder farmers. Most farmers in the ECHO network produce and save much of their own planting seed, and some are in a transition time with using commercial seed for certain crops. Understanding farmer seed access, supplies, and practices is a critical part of improving local farming systems.

Nutrient Quantity vs Access - 01-01-2014

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- Español (es)

- English (en)

- Français (fr)

In order to achieve high levels of agricultural productivity in the tropics at the lowest possible economic and ecological costs, we need to properly understand the relationship between nutrients in the soil and crop productivity. For this to happen, the current understanding needs to change. The conventional view of the relationship between soil nutrients and crop productivity in the tropics is leading to both damaging agricultural policies and inefficient and damaging farm-level practices. There is no need to use the huge quantities of chemical fertilizers that are so often recommended. In fact, often times the use of such fertilizers is unnecessary, expensive and harmful to the environment, especially because farmers often stop using organic matter when they use chemical fertilizers.

Much of the theory described here was originally developed by Drs. Artur and Ana Primavesi. For a much more in-depth analysis of the chemical and biological issues described in this article, the best book at present is Ana Primavesi’s The Ecological Management of the Soil (available in Spanish and Portuguese). This article will discuss the conventional concept of soil fertility and some of its shortcomings; a new conception of soil fertility; and how the new theory can be put into practice.

Zai Pit System - 01-01-2013

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- Français (fr)

- Español (es)

- English (en)

“Zai” is a term that farmers in northern Burkina Faso use to refer to small planting pits that typically measure 20-30 cm in width, are 10-20 cm deep and spaced 60-80 cm apart. In the Tahoua region of Niger, the haussa word “tassa” is used. English terms used to decribe zai pits include “planting pockets”, “planting basins”, “micro pits” and “small water harvesting pits.” Seeds are sown into the pits after filling them with one to three handfuls of organic material such as manure, compost, or dry plant biomass. The following quotes provide further detail.

What’s Inside:

- Introduction

- Historical background

- Technical Details

- How to optimize the zai system

- Other plant basin systems

- References

An Introduction to Wood Vinegar - 01-08-2013

Prakrit Khamduangdao was looking for an alternative to agricultural chemicals to control pests in his vegetable farm. However, he was not completely satisfied with various botanical pest control measures being promoted in northern Thailand. He reports that even though certain natural insect repellents were beneficial, their effects were too limited. Additionally, finding adequate amounts of necessary raw plant materials and processing them into sprays was laborious and time consuming.

When Mr. Prakrit first heard about wood vinegar in 2000 he was intrigued. Compelled by the idea of a natural by-product of charcoal production that can control pests and diseases of crops, he bought his first bottle. Having used the product, Mr. Prakrit was pleased with the ease of mixing and application. Ultimately, after observing much fewer insect pests and fungal diseases on his crops, he became convinced of the effectiveness of wood vinegar.

What’s Inside:

Uses of Wood Vinegar

Wood Vinegar Production

Composition and Characteristics of Wood Vinegar

Wood Vinegar Concerns?

Charcoal Production in 200-Liter Horizontal Drum Kilns - 05-02-2016

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- English (en)

- Français (fr)

- Español (es)

Until recently, firewood was taken for granted in northern Thailand. With vast forests full of many types of trees, upland households could afford to be choosy concerning the wood they used for cooking.

However, in recent years, more and more communities are facing restricted access to forest products due to the establishment of national parks. In many areas, deforestation caused by agricultural activities, such as the encroachment of large plantations, is also resulting in declining access to firewood.

In upland communities, commercial types of cooking fuel like propane are not readily accessible or affordable. With limited options, communities and development organizations have begun considering alternative fuels.

Biochar: An Organic House for Soil Microbes - 01-06-2013

- Điều này cũng có sẵn trong:

- Français (fr)

- Español (es)

- English (en)

Rick Burnette wrote an article for Issue 7 (July 2010) of ECHO Asia Notes, titled “Charcoal Production in 200-Liter Horizontal Drum Kilns.” My article takes the charring process a step further by exploring the rapidly re-emerging world of biochar. Biochar is a form of charcoal, produced through the process of pyrolysis from a wide range of feedstocks. Basically any organic matter can be charred, but agriculture and forestry wastes are most commonly used due to the available volume. Biochar differs most significantly from charcoal in its primary use; rather than fuel, it is primarily used for the amendment of soils (enhancing their fertility) and sequestration of carbon (reducing the amount of CO2 released into the atmosphere).

Biochar has received a lot of interest internationally over the last few years, especially in light of the rising demand for food and fuel crops, and of raging debates on how to radically slow down runaway climate change. With strong voices on both sides of the debate—that is, both in favor of and against the widespread production and application of biochar—I would like to step back to the beginning of the story, hopefully putting things into perspective again.