Les Notes Techniques de ECHO

Les Notes Techniques de ECHO sont des publications spécifiques sur des sujets importants pour ceux qui travaillent dans les régions tropicales et subtropicales. Nos documents sont rédigés par le personnel de ECHO et des rédacteurs externes, tous pétris d’expérience et de connaissances dans leur domaine. Ces documents sont gratuits pour votre usage personnel et nous l'espérons, joueront un rôle précieux dans votre bibliothèque de ressources qui sert à votre travail dans le développement agricole!

100 Problématiques abordées dans cette publication (Affichage des numéro 43 - 34) Précédent | Suite

Filtre à Eau Biosand - 01/01/2001

- Aussi disponible en:

- Español (es)

- English (en)

L’accès à l’eau potable est encore aujourd’hui un des plus grands défis mondiaux. Le filtre BioSand est une technologie disponible pour purifier l’eau à la maison. Il filtre l’eau contaminée à l’aide d’un film biologique naturel et de couches de sable, de cailloux et de pierres. Le filtre BioSand peut être fabriqué avec des matériaux disponibles sur place. C’est un système à faible coût qui élimine les sédiments en suspension et d’autres impuretés de manière à améliorer la qualité de l’eau destinée à la consommation humaine.

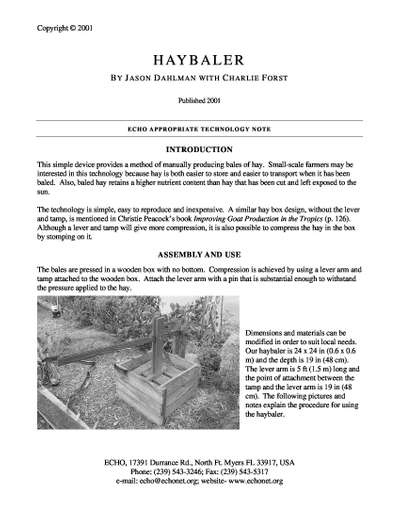

Haybaler - 01/01/2001

This simple device provides a method of manually producing bales of hay. Small-scale farmers may be interested in this technology because hay is both easier to store and easier to transport when it has been baled. Also, baled hay retains a higher nutrient content than hay that has been cut and left exposed to the sun.

Solar Dehydrator - 01/01/2001

Often the biggest challenge faced by a tropical farmer is not in the production of a crop but rather in the preservation of the crop. Farmers may want to preserve a crop for future consumption or for sale at a time when the market will offer a higher price.

Using a solar dehydrator is a simple, cost-effective way to preserve a variety of different crops. Dehydrating removes the moisture from food so that bacteria, yeast and mold cannot grow and spoil it.

Poêles à la Sciure de Bois - 01/01/2001

- Aussi disponible en:

- English (en)

- Español (es)

Ces poêles sont utiles là où le bran de scie est un déchet abondant. Pour faire fonctionner ces poêles, il suffit de bourrer du bran de scie ou un autre combustible similaire dans une structure de briques ou de boîtes à conserves; la flamme est assez propre et ne produit que peu de fumée. Ces poêles peuvent amener à ébullition 4 litres (un gallon) d’eau dans un délai d’environ 12 à 15 minutes et maintiennent une température élevée pendant de deux à cinq heures, selon le type de combustible utilisé et sa densité (le bran de scie fin et très tassé brûle plus longtemps que le matériel grossier ou meuble). En plus du bran de scie, on peut utiliser les résidus de plantes fibreuses comme la balle de riz ou d’autres céréales, l’écorce de grains de café et la paille. Pour rendre le combustible grossier plus compact, on peut y ajouter un peu de bran de scie.

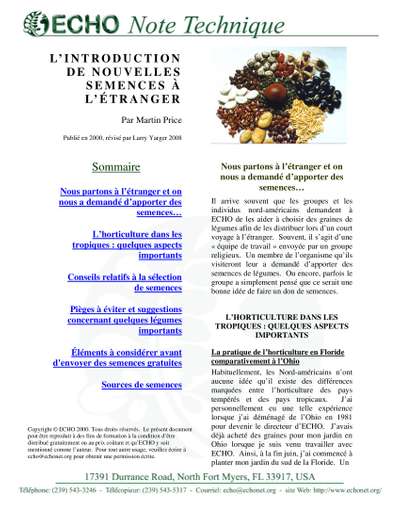

L’Introduction de Nouvelles Semences à l’Étranger - 21/01/2000

- Aussi disponible en:

- English (en)

- Español (es)

Habituellement, les Nord-américains n’ont aucune idée qu’il existe des différences marquées entre l’horticulture des pays tempérés et des pays tropicaux. J’ai personnellement eu une telle expérience lorsque j’ai déménagé de l’Ohio en 1981 pour devenir le directeur d’ECHO. J’avais déjà acheté des graines pour mon jardin en Ohio lorsque je suis venu travailler avec ECHO. Ainsi, à la fin juin, j’ai commencé à planter mon jardin du sud de la Floride. Un homme d’âge mûr m’expliqua : « Ici, en Floride, nous ne pratiquons pas l’horticulture en été. Nous laissons les mauvaises herbes envahir le jardin jusqu’à l’automne. » Cela me laissa perplexe : pourquoi les gens feraient-ils une chose pareille? Malgré ce conseil, je décidai de planter des haricots, des radis, des concombres, des zucchinis, de la laitue, des melons brodés, des brocolis, des choux, etc. Je plantai également des zinnias et des soucis. Le jardin me donna d’innombrables surprises. La chaleur et l’humidité quotidienne de la Floride ne sont qu’occasionnelles en Ohio. Combinées aux pluies fréquentes, elles favorisèrent l’apparition de maladies qui se propagèrent rapidement dans mon jardin. (De nombreux microorganismes ravageurs ne prolifèrent que lorsque la végétation est détrempée.) Comme le sol ne gèle pas, les insectes, les nématodes et les maladies ne sont pas éliminés chaque année durant l’hiver. Certains ravageurs dont je n’avais jamais entendu parler décimèrent mes plantes. Par ailleurs, les rayons du soleil beaucoup plus intenses à cette latitude chauffèrent d’autant plus les feuilles. Beaucoup de mes variétés de plante préférées ne purent supporter la chaleur élevée.

Cashew - 01/01/1999

The cashew, Anacardium occidentale, is a resilient and fast-growing evergreen tree that can grow to a height of 20 m (60 ft). It belongs to the family Anacardiaceae, which also contains poison ivy and the mango. Native to arid northeastern Brazil, the cashew was taken around the world by the Portuguese and Spanish who planted the trees in their colonies. The English name "cashew" is derived from the Portuguese "cajú" which came from the Tupi Indian "acaju" (Rosengarten, 1984). In Spanish it is known as "marañón" or "anacardo."

Cashew is an important nut crop that provides food, employment and hard currency to many in developing nations. Of all nuts, cashew is second only to the almond in commercial importance (Rosengarten, 1984). India, Mozambique, and Tanzania are the three biggest exporters of cashew nuts today. Although there are large commercial plantings of cashew, wild trees or those owned by small farmers account for 97% of cashew production (Rosengarten, 1984).

The plant produces not only the well-known nut, but also a pseudofruit known as the cashew "apple" and cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) which is used for industrial and medicinal purposes.

The cashew tree has other uses as well. It is used for reforestation, in preventing desertification and as a roadside buffer tree. Cashew was planted in India in order to prevent erosion on the coast (Morton, 1960). The wood from the tree is used for carpentry, firewood, and charcoal. The tree exudes a gum called cashawa that can be used in varnishes or in place of gum arabic. Cashew bark is about 9% tannin, which is used in tanning leather.

Egusi Recipes - 01/11/1998

In West Africa, the name Egusi is applied to members of the gourd family having seeds of high oil content. Egusi Melon plants closely resemble watermelon plants; both have a non climbing creeping habit and deeply cut lobed leaves. The pulp of the watermelon fruit, however, is sweet and edible while the Egusi Melon has bitter and inedible fruit pulp. Egusi Melon seeds are larger than watermelon seeds, and they are light colored. Egusi Melon is cultivated in portions of West Africa, especially in Western Nigeria, for the food in the seed and as a crop interplanted with maize, cassava, or other crops.

Le jicama - 01/10/1998

- Aussi disponible en:

- English (en)

Le jicama (Pachyrhizus erosus), un membre de la famille des fabaceae ou leguminosae est une légumineuse vivace de courte durée souvent cultivée en tant que vigne grimpante annuelle. Il fleurit lorsque la durée du jour raccourcit, produisant de longues gousses non comestibles et des tubercules. Chaque plante compte un nombre réduit de tubercules habituellement sphériques, mais souvent lobés et dont le poids total peut atteindre plusieurs kilos. Le tubercule a une chair blanche et croquante même après la cuisson; il est couvert d’une peau ou cortex brun clair facile à éplucher.

Le jicama, (prononcé « hikama »), également appelé pois patate, dolique tubéreux et pois-manioc, est originaire de la Méso-Amérique et naturalisé dans toutes les régions agricoles des tropiques. C’est une excellente plante commerciale là où un marché existe déjà, une culture utile de la ferme pour diversifier le régime alimentaire et un nouveau légume à usages spéciaux à cause de son goût agréable et de sa texture croquante.

Quail: An Egg & Meat Production System - 01/09/1998

Many families in the tropics must assume a major role in production of their own foodstuffs. Incomes are so low that purchase of food competes with purchase of necessary items that cannot be hand-made. Most governments in the tropics do not have the resources to guarantee even minimum food to all of their citizens. Families in rural and urban situations often live in a minimum of space without soil that can be cultivated, or even a backyard in which a few animal cages can be placed. Such persons sorely need small scale systems that are in harmony with resources available.

Unfortunately, not enough study has been given to small-scale production systems. The small animals typically encountered on almost every small farm, chickens, ducks, geese, and rabbits, are still too large for many households. A small animal for a minimum sized system should produce food in units that can be eaten at one meal so that refrigeration is not necessary. Furthermore, such systems should use resources available to most families, including feeds that can be grown or purchased, cages that are home made, and systems of sanitation that

protect the health of the animals and the residents of the household. The development of such systems has not attracted serious investigators.

The system described here, based on the Japanese quail, Coturnix japonica, is based on sound published information on this species and its requirements, and on three years of experimentation with quail at the household level. All apparatuses described were built and used, and actual costs and yields are reported.

Banana, Coconut & Breadfruit - 01/06/1998

- Aussi disponible en:

- English (en)

- Español (es)

There are more than one hundred major species of fruits in the tropics, which make a very interesting contribution to the appetite as well as to good nutrition. These species vary in ecological requirements, in season of production, in yields, uses and, of course, in many other characteristics. The three fruits that are the subject here are outstanding fruits that are particularly important in feeding people. These fruits also produce a lot of food for a minimum of effort. In fact, they are practically staple fruits of the tropics. In contrast, mangoes are very important in the tropics, but are seldom a staple. Citrus fruits are varied, widely produced and enjoyed, but never a staple. These comments can be extended to many other fruits as well.

Probably the most important fruit in the tropics in terms of distribution, use and contribution as food is the banana (for purposes of this discussion, bananas and plantains will be considered together). The many ways these fruits can be eaten makes them a popular everyday food. Its primary nutritional contribution is calories (as starch and sugar).

The coconut is common and a daily food in some but not all parts of the tropics. It is well adapted and can be grown almost anywhere. The tree itself is versatile in its application and may be the most useful tree of the tropics. The fruit is used at all stages in unique ways, and is a significant source of protein and a major source of fat in the diet.

The breadfruit, aptly named, a staff of life in the Pacific. Its nature as a staple is the reason that it has been so widely introduced throughout the tropics. Normally seasoned, primitive and modern methods of processing have been developed, and native cooks find diverse uses for the fruit. Its contribution to the diet is principally starch, and ripe fruits are rich in sugar as well.