- ECHO's Seedbank Has Foil-Lined Seed Packages

- Basic Seed Harvest Guidelines from ECHO's Seedbank

- Rules of Thumb for Seed Storage Conditions

- Book Review: The Community Seedbank Kit

- Book Review: Lost Crops of the Incas

- Book Review: Lost Crops of Africa. Volume 1: Grains

ECHO'S SEEDBANK HAS FOIL-LINED SEED PACKAGES. The lengthy trip in the mail and, sometimes, time sitting on your shelf waiting for the rainy season, is hard on seeds. The two best ways to increase the life of seeds are to reduce moisture and temperature. The foil in our seed packages forms a moisture barrier. Each seed lot is dried and treated with insecticide and fungicide. Seeds are measured into labelled packets, which are sealed with a quick brush of an iron (like those used to iron clothes). If you can put the sealed packets in a refrigerator you should have a much improved chance of good germination. You can reseal them with an iron if you wish.

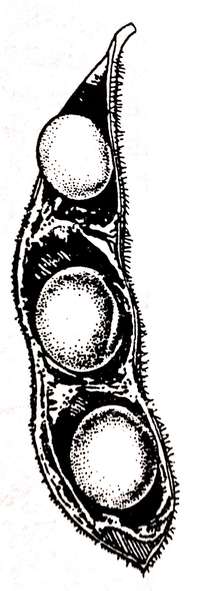

BASIC SEED HARVEST GUIDELINES FROM ECHO'S SEEDBANK. For plants with seeds that mature and dry on the plant, like corn, beans, amaranth, millet, sorghum, peas, lettuce, tarwi, kaniwa, etc.: Only harvest fully mature seed. The plant may start to die before the seed is ready. Harvest seed when dry (not wet with  morning dew or after a rain). A good guide is when the first seeds are exposed or shatter (fall to the ground), as with the grains, or when pods are brown and crisp, for beans. (Amaranth can be a difficult plant to harvest--keep a close eye on it so you don't miss the seeds and lose them as they fall; you may even need to "milk" the seed clusters a few times to get the seed as it matures.) To avoid bean borers and fungal problems, however, it is best to harvest continuously toward the end of the season, so mature seeds do not stay in the garden too long. Many of these seeds can simply be threshed or shelled and cleaned from debris by winnowing with the wind or a fan.

morning dew or after a rain). A good guide is when the first seeds are exposed or shatter (fall to the ground), as with the grains, or when pods are brown and crisp, for beans. (Amaranth can be a difficult plant to harvest--keep a close eye on it so you don't miss the seeds and lose them as they fall; you may even need to "milk" the seed clusters a few times to get the seed as it matures.) To avoid bean borers and fungal problems, however, it is best to harvest continuously toward the end of the season, so mature seeds do not stay in the garden too long. Many of these seeds can simply be threshed or shelled and cleaned from debris by winnowing with the wind or a fan.

For plants with fleshy fruits, like gourds, squashes, pumpkins, and peppers: Be patient. Only harvest fully mature fruits. The plant may be completely dead by the time the seed is ready for  harvest. Remove fruits from plants and allow them to get soft, past the point you would want to eat them (except pumpkins, which do not soften, but do ripen during a few months after removal from the vine). Seeds are perfect for harvest if they separate easily from the flesh when rubbed out under water, for example. Scoop all the seeds and flesh into a large bowl or bucket of water, and work the seeds free with your fingers. Healthy, mature seeds will usually sink, although if all the floating seeds look better than those sinking, the case may be reversed for your plant. (Sometimes, good pumpkin seeds may float, while dead ones sink. Many cucurbit seeds, among others, have a 'dormant' period after harvest, so wait a few months to test the germination. In one case, freshly harvested, dried pumpkin seeds had zero germination, but another test several months later had over 80% germination.) This makes it very easy to clean the seed: simply rub the flesh away from the seeds, and tip the dirty water and flesh off the top; add more water, swirl the bowl, and pour off that water; continue for a few more washes until only the seed is left at the bottom; strain and dry immediately. Please note that seeds should not be left in the water for a long time, as they may absorb water, swell, and start to germinate. Some seeds benefit from a period of "fermenting" in the water before cleaning the seeds from the fruits; in tomato, for example, this treatment is said to reduce some of the diseases which can affect the seedling during germination.

harvest. Remove fruits from plants and allow them to get soft, past the point you would want to eat them (except pumpkins, which do not soften, but do ripen during a few months after removal from the vine). Seeds are perfect for harvest if they separate easily from the flesh when rubbed out under water, for example. Scoop all the seeds and flesh into a large bowl or bucket of water, and work the seeds free with your fingers. Healthy, mature seeds will usually sink, although if all the floating seeds look better than those sinking, the case may be reversed for your plant. (Sometimes, good pumpkin seeds may float, while dead ones sink. Many cucurbit seeds, among others, have a 'dormant' period after harvest, so wait a few months to test the germination. In one case, freshly harvested, dried pumpkin seeds had zero germination, but another test several months later had over 80% germination.) This makes it very easy to clean the seed: simply rub the flesh away from the seeds, and tip the dirty water and flesh off the top; add more water, swirl the bowl, and pour off that water; continue for a few more washes until only the seed is left at the bottom; strain and dry immediately. Please note that seeds should not be left in the water for a long time, as they may absorb water, swell, and start to germinate. Some seeds benefit from a period of "fermenting" in the water before cleaning the seeds from the fruits; in tomato, for example, this treatment is said to reduce some of the diseases which can affect the seedling during germination.

SURFACE CLEANING. Seeds are treated in an antibiotic solution (10% bleach is good) for 2 minutes. This eliminates much of the bacteria or fungi from the seed surface. (Vinegar has some antibiotic action. If that is all you have available you might wish to experiment on a small scale to determine how much you could use without reducing viability. I do not know how effective this would be.) Seeds are then washed in clean water.

DRYING. Be sure seeds are completely dry before storage. (Fruit seeds are exceptions to this rule, as many do not survive drying; see below.) This is best accomplished slowly and gently; after threshing or cleaning, allow most seeds about a week in a very dry place for this process to be complete.

Some basic principles to keep in mind: Once a seed is dry, it is best to keep it dry, even if that means leaving some chaff in  with the seed or leaving a bit of dried "skin" on the seed. Do not re-moisten seed once it has begun to dry. Internal moisture is more damaging to seeds in storage than heat. Your seed may dry adequately simply by spreading it out on a screen in the sun for a day or two; avoid oven-drying, as it is often too fast or hot and can kill the seeds. Temperatures over 96 deg.F can damage seeds. Stir drying seeds once a day to ensure even drying. Dry seeds break rather than bend and shatter when hit with a hammer. Then store the seeds in airtight containers with proper labels identifying the seed and date of harvest. Store in a cool, dry place if that is available. The humidity is the most critical factor; seeds can live in hot, dry deserts for much longer than in a cool but damp environment.

with the seed or leaving a bit of dried "skin" on the seed. Do not re-moisten seed once it has begun to dry. Internal moisture is more damaging to seeds in storage than heat. Your seed may dry adequately simply by spreading it out on a screen in the sun for a day or two; avoid oven-drying, as it is often too fast or hot and can kill the seeds. Temperatures over 96 deg.F can damage seeds. Stir drying seeds once a day to ensure even drying. Dry seeds break rather than bend and shatter when hit with a hammer. Then store the seeds in airtight containers with proper labels identifying the seed and date of harvest. Store in a cool, dry place if that is available. The humidity is the most critical factor; seeds can live in hot, dry deserts for much longer than in a cool but damp environment.

The bean seedbank at CIAT in Colombia places dry seeds in a chamber containing a desiccant to reduce moisture below 10%. This has probably been achieved if the color indicator on the desiccant has not changed over a period of about 5 days with the seeds present. In the past, we adapted this procedure, placing dried seeds in a small open container on top of some Drierite in the bottom of a large-mouth peanut butter jar with the lid tightly closed. We mixed a small amount of the more expensive colored indicator with the inexpensive white Drierite. If the blue turned to pink in only a couple days, we replace the Drierite. Once it remained blue for nearly a week we assumed that moisture content of the seeds was below 10%. If you cannot purchase Drierite or other desiccant, Organic Gardening magazine says that you can use an equal volume of powdered milk (perhaps with a few crystals of indicator desiccant thrown in?). Desiccant (or milk, rice, etc.) can be rejuvenated by heating for a time in an oven at a low temperature. You may be able to locate some kind of desiccant at a nearby medical clinic.

RULES OF THUMB FOR SEED STORAGE CONDITIONS. We contacted two knowledgeable seed experts for details. Bob Heisey with Peto Seed Company, a supplier to the major retail seed catalogs, said that if saving seed for only a few years (not for decades, as in projects to preserve rare varieties), you can use this rule of thumb to store on open shelving in an air-conditioned room: the temperature in Fahrenheit plus the relative humidity should be less than 100. For example, if I can afford to keep a room at 70 deg.F I would need to get the relative humidity to 30 or lower. [For those who have forgotten the formula, you can convert Centigrade to Fahrenheit as follows: F = 9/5 C + 32.] If the humidity of the entire room cannot be lowered that far, you can store seed in airtight containers together with a desiccant to absorb excess moisture. Effective desiccants include charcoal, powdered milk, rice or other material which you have noticed absorbs water. The desiccant should first be dried at very low setting in an oven.

RULES OF THUMB FOR SEED STORAGE CONDITIONS. We contacted two knowledgeable seed experts for details. Bob Heisey with Peto Seed Company, a supplier to the major retail seed catalogs, said that if saving seed for only a few years (not for decades, as in projects to preserve rare varieties), you can use this rule of thumb to store on open shelving in an air-conditioned room: the temperature in Fahrenheit plus the relative humidity should be less than 100. For example, if I can afford to keep a room at 70 deg.F I would need to get the relative humidity to 30 or lower. [For those who have forgotten the formula, you can convert Centigrade to Fahrenheit as follows: F = 9/5 C + 32.] If the humidity of the entire room cannot be lowered that far, you can store seed in airtight containers together with a desiccant to absorb excess moisture. Effective desiccants include charcoal, powdered milk, rice or other material which you have noticed absorbs water. The desiccant should first be dried at very low setting in an oven.

Ron Hurov, a botanist formerly in the seed business, believes that this rule of thumb is not adequate. He says that the main objective in storing seed is to reduce respiration. This is accomplished in three ways; adjusting temperature, humidity, and oxygen levels where seeds are located. Temperature: All seeds should be stored just above freezing level (34-35 deg.C). An inexpensive walk-in unit or commercial refrigerator is sufficient. Humidity: Through Ron's experience, he has characterized seed into three areas: wet, semi-wet, and dry. The rule of thumb here is to copy a plant's natural environment. If the plant likes it wet, such as the botanical family Araceae, then store the seeds in water. A semi-wet example would be the Citrus family. A plant family stored in dry conditions is Leguminoseae. Oxygen: Seeds should be kept in airtight containers free of oxygen. Vacuum sealing is ideal. A cheap ($150) vacuum sealer/dryer can be purchased through a health food company. The best suggestion for an airtight container is a mason jar. Ziploc bags and other plastic containers are not good enough.

THE COMMUNITY SEEDBANK KIT. Millions of people have been fed by the higher yields as farmers switched to new  "green revolution" varieties. But what happens to all those varieties that farmers used to grow? Some of them are the result of plant selection through centuries. "The introduction of modern grain varieties in the Mid East has led to widespread losses of traditional varieties. African rice is nearly extinct in its native homelands. ...avariety called IR-36 now extends over 60% of the rice lands of Southeast Asia where, only a few years ago, thousands of farmer varieties were common. ...the black beauty egg plant is ... destroying its own diversity in the Sudan."

"green revolution" varieties. But what happens to all those varieties that farmers used to grow? Some of them are the result of plant selection through centuries. "The introduction of modern grain varieties in the Mid East has led to widespread losses of traditional varieties. African rice is nearly extinct in its native homelands. ...avariety called IR-36 now extends over 60% of the rice lands of Southeast Asia where, only a few years ago, thousands of farmer varieties were common. ...the black beauty egg plant is ... destroying its own diversity in the Sudan."

These lost varieties may have traits that would be invaluable if, for example, a new disease strikes. One of those varieties might be much better adapted to difficult growing conditions in another part of the country that wishes to begin growing the crop. They will also be invaluable to producing future "green revolution" crops. This loss of genetic diversity is of equal concern to the small farmer, the international center and the big seed company.

The purpose of the Community Seedbank Kit is to help private volunteer agencies develop community seedbanks to collect, preserve and assure easy community availability of seeds of crops in their region before further "genetic erosion" takes place. The kit is not a book. Rather, it is a loose collection of several 4-15 page sections. Topics include: Building the bank (the need); Building the bank (practical); The role of the voluntary agency; Sources and resources; Overview and issues.

The section on building the bank (practical) discusses how to select the crops to be collected, timing the collection, the collection strategy once you are in the field, documentation, seed cleaning and drying, seed storage, collection grow-outs and a table indicating whether a seed is self- or cross-pollinated and its relative storability index.

If you can envision your organization undertaking such a project, the kit will be a great help. They anticipate future revisions. If those include some case studies and greater detail on practical techniques such as testing seed viability and appropriate technology alternatives to seed drying and storage, the kit will be even more helpful. The price is $4.50 in North America, or $8.50 (including airmail) elsewhere. Indicate whether you prefer English, French or Spanish. Order from Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI-USA), P.O. Box 655, Pittsboro, NC 27312; phone 919/542-1396.

LOST CROPS OF THE INCAS. The National Research Council of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences produced this book, and it is one of their best in the underexploited plants series. This series opened for me the world of plants that God has given to humanity which are still used in only a few countries and are little known elsewhere. This series ultimately led ECHO to establish our seedbank of underexploited plants. If you write to ECHO for information on any of the Andean crops, we will probably turn here first to answer your questions.

This book, written under the leadership of Dr. Noel Vietmeyer and a panel of experts, takes a close look at the wealth of plants native to the Andes mountains of South America. The region that gave us the pepper and potato has a lot more yet to offer. All together, 31 little-known fruits, nuts, grains, legumes, vegetables, and root crops are described in some detail. A chapter is devoted to each plant and includes a general introduction; prospects for the crop in the Andes, other developing countries, and industrialized regions; the plant's uses, nutrition, agronomy, harvesting, and limitations; and research needs. Chapters end with a short synopsis useful for people interested in growing the plant. Each chapter is well-illustrated with several  photographs and drawings. The book provides an introduction to and stimulates interest in these crops, providing a valuable overview.

photographs and drawings. The book provides an introduction to and stimulates interest in these crops, providing a valuable overview.

With the notable exceptions of the pepper and potato, Andean crops are seldom seen outside their native habitat. This is surprising in light of the wealth of crops that were developed over the centuries under the extremes of soil, rainfall, and temperatures of the Incas' vast empire. Many of the crops are quite nutritious and have only recently attracted the attention of researchers, but have the potential for worldwide usefulness.

Root crops include: achira (Canna edulis), containing a starch with unusually large grains; ahipa (Pachyrhizus ahipa), a legume whose sweet roots remain crunchy even after cooking; arracacha (Arracacia xanthorrhiza, pictured), carrot-like roots that can be boiled as a table vegetable; maca (Lepidium meyenii), a sweet, tangy delicacy in the highlands; mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum), a staple that requires little labor; mauka (Mirabilis expansa), a "cassava of the highlands" that turns sweet after lying in the sun; oca (Oxalis tuberosa), a very hardy staple; little known potatoes (Solanum sp.) that have potential as germplasm; ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus), a brightly colored source of carbohydrates; and yac¢n (Polymnia sonchifolia), a sweet, yet almost calorie-free tuber.

Legumes detailed in the book include: basul (Erythrina edulis), a tree with large edible seeds; nunas or popping  beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), which are popped rather than boiled and make a tasty snack; and tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis), a lupine richer in protein than beans and peanuts with as much oil as soybeans. Vegetables include lesser-known peppers (Capsicum sp.) and squashes (Cucurbita sp.).

beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), which are popped rather than boiled and make a tasty snack; and tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis), a lupine richer in protein than beans and peanuts with as much oil as soybeans. Vegetables include lesser-known peppers (Capsicum sp.) and squashes (Cucurbita sp.).

Several fruits have particular promise, especially in specialty markets: unusual or large berries (Vaccinium sp., Myrtus sp., and Rubus sp.); capuli cherries (Prunus capuli), a popular city tree; cherimoya (Annona cherimola, pictured), a delicious fruit grown commercially in the Mediterranean; goldenberries (Physalis peruviana), a very flavorful jam berry; highland papayas (Carica sp.), which have potential as germplasm; lucuma (Pouteria lucuma), a staple fruit which bears year round; naranjilla (Solanum quitoense), a good fruit for juices; pacay (Inga sp.), a sweet-fleshed pod; passion fruit (Passiflora sp.) that are superior to most commonly known cultivars; pepino (Solanum muricatum), a prospect for premium fruit; and tamarillo (Cyphomandra betacea), a popular juice fruit.

Three grains were also researched: kaniwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule), a nutritious grain with 16-19% protein; kiwicha (Amaranthus caudatus), with good quality protein high in lysine; and quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), a better-known protein source. Two nuts are listed as well: Quito palm (Parajubaea cocoides), a high producer of tiny coconuts; and walnuts (Juglans neotropica), a fast-growing tree with good quality nuts.

It is particularly difficult for ECHO to keep seed in our seedbank of Andean crops, as most of them do not produce seed in Florida. With some exceptions, high altitude crops are the most difficult in the world for us to propagate. Between Florida's normal seasons and our "semi-arid" and "rain forest" greenhouses, we can duplicate many climates. Duplicating a very long but cool growing season is our greatest challenge. If you work in the Andes and would be willing to supply us with seed for crops, ask for our "Andean seeds wish list" and we will send you a plant import permit.

The book (415 pp.) is being reprinted with color photocopies by Craig Dremann at Redwood City Seed Co., Box 361, Redwood City, CA 94064, USA; phone 415/325-7333. Cost is $40 including surface mail. For airmail add: Americas, $12; Europe, $16; Pacific Rim, $20. His home page is http://www.Batnet.Com/rwc-seed/.

LOST CROPS OF AFRICA. VOLUME 1: GRAINS (383 pp.) is the newest in the National Academy of Sciences series on very promising but little-known or neglected species. Writing was funded by USAID. This inspiring volume (the first of three which are planned) discusses the potential of African grains for producing food and other products in Africa and around the world.

The series is "intended as a tool for economic development" among those who may promote these crops for local cultivation,  develop markets for the grains, and explore the multiple uses of these species. The species discussed in this series were selected from nominations by people around the world. The information given about the crops helps readers to understand and appreciate the unique value of each plant and evaluate its potential for a given area. There are also very insightful appendixes on "potential breakthroughs" in some of the most pressing problems for development workers, including grain handling and child nutrition.

develop markets for the grains, and explore the multiple uses of these species. The species discussed in this series were selected from nominations by people around the world. The information given about the crops helps readers to understand and appreciate the unique value of each plant and evaluate its potential for a given area. There are also very insightful appendixes on "potential breakthroughs" in some of the most pressing problems for development workers, including grain handling and child nutrition.

The species covered include: African rice, finger millet, fonio (acha), pearl millets, sorghums (subsistence, commercial, specialty, and fuel and utility types), tef, other cultivated grains (guinea millet, emmer, irregular barley, and Ethiopian oats), and wild grains. These plants offer much promise because they tolerate many extreme growing conditions and produce well with minimal inputs. They are generally nutritious and offer new flavors. They also offer other benefits; for example, the "fuel and utility sorghums" are used as firewood, liquid fuels, soil reclamation, wind erosion protection, weed control, crop support, fibers, brooms, and animal feeds. As with all the NAS books, further reading and many research contacts are given for each crop.

Readers in Western countries can purchase the book for $24.95 plus $4.00 surface postage and handling. Noel Vietmeyer and Mark Dafforn with the National Research Council told us they can think of no group more likely to make use of this book than those of you in ECHO's network who work in Africa. So they will donate enough books to send you a free copy while our supply lasts. IF you are already a member of ECHO's overseas network working in any third world country you may request one free copy of the book by writing clearly the address where the book is to be sent and enclosing postage if your work is not in Africa. For addresses in Africa only ECHO will pay surface postage. For all others (and in Africa if you want airmail) please send appropriate postage: surface $4; airmail Latin America, $6.00; airmail Europe, $11.00; airmail Africa and Asia, $11.70. MasterCard and Visa or checks in US dollars written on a US bank are the only payments we can accept.