- Beekeeping & Development, An "EDN" for Beekeepers

- Independent Study Course on Tropical Beekeeping

- Book Review: Beekeeping of the Assassin Bees/La Abeja Africanizada

- Is the Neem Tree Harmful to Honeybees?

- When Honeybees Become Drunk

- How do the Africans Handle African Bees?

- One Experience With Bees in Africa

- Stopping Bees

BEEKEEPING & DEVELOPMENT, AN "EDN" FOR BEEKEEPERS. This quarterly networking newsletter specializes in information related to all aspects of beekeeping in the tropics and subtropics. A typical issue contains: news briefs related to past, present, and future happenings around the world; practical beekeeping tips, like how to make your own smoker, how to build a hive out of mud bricks and concrete, and queen rearing with African bees. Feature articles deal with case studies and special issues (e.g. tropical trees for beekeepers). Useful bits of information related to job openings, books, meetings and resources of interest to beekeepers in the tropics round out each issue.

One tidbit we recently picked up is how to use a paper clip (with 4 mm inner measurement) as a queen excluder. Newsletter  subscriptions (4/year) are L16.00 (US$35). Folks living in developing countries may also pay by beeswax barter or request a sponsored subscription. In addition to the newsletter, they distribute a variety of educational materials, provide free expert advice to those on the field and can assist in project planning and implementation, teaching, organizing seminars, preparing documentation, etc. Write Bees For Development, Troy, Monmouth, NP5 4AB, UK; phone: 44(0) 16007 13648; fax: 44(0) 16007 16167; e-mail 100410.2631@CompuServe.COM.

subscriptions (4/year) are L16.00 (US$35). Folks living in developing countries may also pay by beeswax barter or request a sponsored subscription. In addition to the newsletter, they distribute a variety of educational materials, provide free expert advice to those on the field and can assist in project planning and implementation, teaching, organizing seminars, preparing documentation, etc. Write Bees For Development, Troy, Monmouth, NP5 4AB, UK; phone: 44(0) 16007 13648; fax: 44(0) 16007 16167; e-mail 100410.2631@CompuServe.COM.

INDEPENDENT STUDY COURSE ON TROPICAL BEEKEEPING. The University of Guelph publishes many independent study courses on topics in agriculture. The course "Tropical Beekeeping" was written by Dr. Townsend who wrote the article on trees for beekeepers in EDN. It is based on his experiences in directing apiculture programs in Kenya and Sri Lanka and consulting in South and Central America and elsewhere. It details the behavior, management and pests of the African, Asian and Africanized bees, and examines beekeeping in the South Pacific and Caribbean. Processing, marketing, hive designs and protective equipment are also covered. There are 120 color slides on microfiche, a text, a cassette tape and a fiche viewer. The cost is C$70, (about US$50) including surface postage. Write to Independent Study, OAC ACCESS, Univ. of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario N1G 2W1, CANADA; e-mail to request a catalog is handbook@access.uoguelph.ca. They also have an advanced apiculture course for C$225 (Tropical Beekeeping is the last part of the latter).

BEEKEEPING OF THE ASSASSIN BEES/LA ABEJA AFRICANIZADA. (Review by Dr. David Unander.) Since being introduced into Brazil in 1957, African honeybees have been spreading through the tropical and subtropical parts of the Americas. They readily interbreed with the honeybees of European ancestry, so that today it is correct to speak of the honeybees through much of Latin America as being Africanized; that is, most of the wild bees and many of the bees in hives now have at least some African ancestry and behavior traits.

Can Africanized bees be successfully kept, or are they too dangerous? The newspaper where I live, normally not overly hysterical, once devoted the cover story of its Sunday magazine to predictions of great personal danger to citizens and grave economic loss to farmers as the "killer bees" begin to arrive in California. Dr. Dario Espina-Perez, a Latin American entomologist and beekeeper, disagrees strongly with this B-movie scenario in his excellent book.

He begins with a very interesting chapter on tropical apiculture (beekeeping) per se. He discusses, for example, problems with heat, humidity, termites and dry seasons; various options for hive construction; how to move established wild colonies from  undesired places, such as the eave of a house, to a hive; evaluating the apiculture potential of a region; and problems from agricultural insecticides. A chapter on African honeybees describes in what ways they differ from their European cousins. In particular, they are smaller, tend to swarm more often, are more aggressive and seem to produce 50-100% more honey.

undesired places, such as the eave of a house, to a hive; evaluating the apiculture potential of a region; and problems from agricultural insecticides. A chapter on African honeybees describes in what ways they differ from their European cousins. In particular, they are smaller, tend to swarm more often, are more aggressive and seem to produce 50-100% more honey.

He carefully makes the point that all bees are aggressive some of the time. The aggression of Africanized bees has been found to vary with region and altitude. The higher the altitude, for example, the more pacific their behavior becomes. (I hope this is good news for some of you living in mountainous areas). Like all honeybees, they are most aggressive when they perceive their hive as being threatened, and least aggressive when collecting pollen (unless directly stepped on). There is a chapter on bee aggression; how it is regulated in the hive, how a stinger works, different human reactions to the venom, including allergic reactions and, of great value, a list of medications to have on hand for various numbers of stings and reactions to them.

After this foundation, there are four chapters with recommended management techniques for Africanized bees organized under: (a) controlling aggression, (b) controlling swarming, (c) controlling migration, and (d) miscellaneous tips. He has a well-developed plan for maintaining breeding colonies of both European-ancestry and local Africanized bees, with hives for honey production using hybrid bees. There is a good discussion of where to place--and where not to place--Africanized hives. For example, Africanized bees do not like vibrations from highways nor strong smells of any origin near the hive. Also there is a review of necessary bee-keeping equipment. I learned that Africanized bees react most negatively to dark colors, better to white, and best of all to orange. There are various recommendations for hive dimensions and openings, honey harvesting schedules, keeping track of new queens, and other management techniques, in order to control the swarming and migratory tendencies of these bees.

Additional ideas are contained in five appendices. There are also some pages of references. One appendix contains the minutes from a question and answer session between Honduran beekeepers and a round table of entomologists and beekeepers experienced with Africanized bees, followed by detailed recommendations for Honduras beekeepers which were worked out at that meeting.

Excellent diagrams and photos illustrate successful apiculture operations with Africanized bees by various Latin American beekeepers. There are also photos of hive structures he advises against. Although the Africanized bees are not the "killer bees" of Hollywood, it seems clear that their aggression merits enough respect that some low-cost apiculture techniques which were previously acceptable in the Americas are no longer safe; beekeeping will now need greater forethought and some additional equipment.

La Abeja Africanizada by Dario Espina P., 158 pp., US$4; or Beekeeping of the Assassin Bees, 170 pp., US$6 are published by Instituto Technologico de Costa Rica, Editorial Technologica de Costa Rica, Apartado 159-7050, Cartago, COSTA RICA. If you are a beekeeper in the Americas, it would be a good investment.

Dr. Hal Reed, an entomologist at Oral Roberts University, wrote, "The review states that the Africanized bees readily interbreed with honey bees of European ancestry. This is not entirely correct. Recent evidence published in Nature and discussed at the recent National Entomology meeting indicate that very little interbreeding is taking place between the European and African strains. Indeed, researchers feel that the leading edge of the invasive population in Mexico is almost purely African, like the original bees introduced in Brazil. There is disagreement about the degree, if any, of interbreeding."

Dave Unander wrote, "Debate continues among scientists regarding the extent to which the African bees are hybridizing with European bees as they migrate northward. (All honeybees in the Americas are believed to have been introductions since Columbus.) If there is substantial mixing of the populations, it is hoped that the undesired behavioral traits of the African bees, such as aggressiveness, might be modified. At this time evidence seems to suggest that bees of purely African ancestry out-compete the hybrid African-European bees. Several prominent bee scientists believe they have data, however, suggesting that the advancing bees are hybrids. Whether they are or not, they so far do not seem to be changing their behavior. So all of the changes in beekeeping methods recommended by Dr. Espina continue to be relevant. As of the summer of 1991, African bees have entered the United States and are expected to ultimately establish themselves from throughout the southern USA to the temperate region of Argentina."

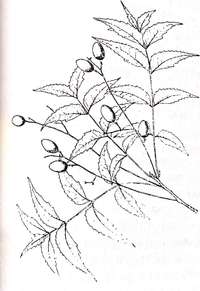

IS THE NEEM TREE HARMFUL TO HONEYBEES? Dave Morneau in the Central Plateau of Haiti asked us about the Haitian beekeepers' belief that neem (Azadirachta indica) or chinaberry (Melia azedarach) blossom nectar is harmful to  honeybees, since leaves and seeds are widely used to control insects. We checked ECHO's library and found no written evidence to support this concern.

honeybees, since leaves and seeds are widely used to control insects. We checked ECHO's library and found no written evidence to support this concern.

Neem: A Tree for Solving Global Problems reports that neem is benign to most beneficial insects, and "[insects] that feed on nectar or other insects rarely contact significant concentrations of neem products." The authors cite a study which found that "only after repeated spraying of highly concentrated neem products onto plants in flower were worker bees at all affected. Under these extreme conditions, the workers carried contaminated pollen or nectar to the hives and fed it to the brood. Small hives then showed insect-growth-regulating effects; however, medium-sized and large bee populations were unaffected."

Beekeeping in India mentions that neem is an erratic producer of nectar, but that the chinaberry does not seem to be visited by bees. Another source lists neem in its list of common nectar sources for Sri Lanka, flowering in May and June. A table in Agroforestry in Dryland Africa shows that providing fodder for bees is a major use of neem and a secondary use of chinaberry. Finally, the thorough Handbook of Plants with Pest-Control Properties does not include either neem or chinaberry in its group of plants which are toxic to honeybees. A visitor from India told us that bees are used to pollinate the extensive neem orchards in his area. Based on our research, we cannot confirm the Haitian farmers' concern that neem could harm their beehives.

Dr. Nicola Bradbear with Bees for Development responded to this article. "Here at Bees for Development we have never received information that either [neem or chinaberry] is harmful to bees. On the contrary, both are frequently cited as excellent sources of pollen and nectar for honeybees (see for example Honeybee Flora of Ethiopia pp. 340-345). It would not be in the interest of flowering plants to produce pollen and nectar that are toxic to possible pollinating insects. ...In Beekeeping and Development 27 we carried news of research in India which indicated that [spraying with] neem derivatives did not deter three bee species from visiting coconut spathes having receptive female flowers with nectar. However the research did not indicate whether the derivatives were toxic to the bees."

WHEN HONEYBEES BECOME DRUNK. According to the October 1992 issue of Apis, drunk bees can be a problem. An Australian scientist studying beekeeping practices in Kenya observed strange behavior. Drunk bees had difficulty coordinating their actions. They may die or be unable to return to their hive. When they do make it to the entrance, strange acting drunk bees are rejected by the guard bees. Finally, drunk bees are more vulnerable to predators.

Apparently local beekeepers were feeding hives weak sugar solutions, which often fermented. Fermentation of weak sugar syrup can be avoided by feeding bees stronger solutions and/or ensuring that the sugar water is consumed quickly. "Because many beekeepers do feed sugar syrup during marginal times, this brings into focus another possible reason colonies might suffer either autumn collapse or spring decline in population."

HOW DO THE AFRICANS HANDLE AFRICAN BEES? I know of folks in the Americas who are giving up beekeeping because of problems that arose when the African bees migrated into their areas. On the other hand, a beekeeper told me of a government project that was proposed to some farmers in Argentina some time ago to supposedly get rid of the African bees there. The beekeepers were not interested because of the higher yields of honey with the African bees. Our readers in Africa work with these bees all the time, so I wrote to Neal Eash in Botswana and asked if he could recommend a practical beekeeping guide for handling African bees. He sent us an excellent book called the "Beekeeping Handbook." You can order it from the Beekeeping Officer, Dept. of Field Services, Ministry of Agriculture, Private Bag 003, Gaborone, BOTSWANA, Southern Africa. You can order them for $2 each, postage paid by surface mail. There is a discount price of $1.50 for 10 or more books.

I think you will find this basic 76-page book to be an excellent and practical guide. It is especially surprising to see pictures of men and boys wearing short-sleeved shirts and shorts handling the African bees. Neal wrote, "My father kept bees. I remember putting on coveralls and heavy gloves, tying pant legs and shirt sleeves and we still got stung. It took a little courage here the first time I worked with bees in a pair of shorts, a T-shirt and straw hat, but I rarely get stung by this so-called 'vicious' bee anymore." He did mention that he recently was stung 7 times when a frame broke just as he ran out of smoke. The Heifer Project Exchange says the book can also be ordered from International Bee Research Assoc., Hill House, Gerrards Cross, Bucks SL9 ONR, ENGLAND.

ONE EXPERIENCE WITH BEES IN AFRICA. Herb Perry gave us this report of an experience with bees while at the Mt. Silinda Mission in southeastern Zimbabwe, located in a subtropical rain forest at 1500m elevation. "One day on returning to my home in a car, I found a large group of African children along with my own children inside the house where my wife was busy extracting bees from the children's hair. It seems they were all playing outside when suddenly the bees attacked and the children all ran screaming into the house. Once inside my wife took to dunking the children's heads in basins of water in an effort to remove the bees from the hair in which they were lodged. This seemed to work, but of course the bees' stingers remained in the scalp and the bees soon died. For about half an hour in the vicinity of our home, nothing moved without being attacked by an angry horde. After things had quieted down somewhat I ventured outside to survey the area. We had a flock of chickens, and they were all dead. We also had a cat which had recently produced a litter of kittens. The mother cat had disappeared into the forest, but the kittens were all dead. The mother returned eventually, but had been stung repeatedly all over her head. Our dog suffered the same fate. He also sought refuge in the forest, and also returned with many stings on his face. Laundry that had been hung on a line to dry, and which had blown in the breeze, had also been stung. The bees appeared to attack anything that moved. We can only guess at what made them become so ferociously hostile, but it has been suggested that perhaps a chicken had eaten one, or someone had carelessly swatted one. At any rate it was a terrifying experience for everyone, especially the children and the animals.

"In spite of the perils involved, many African families would harvest the honey from these wild bees whose hives were generally to be found in hollow trees in the forest. The honey was always very dark, very much like molasses in appearance. Generally speaking the honey would be gathered during the early morning or late afternoon, suggesting perhaps that the bees are inclined to be more docile during these periods."

STOPPING BEES. Suppose a situation arises where you must quickly eliminate an exposed group of bees. For example, a swarm is hanging in a school yard or a truck carrying hives has upset. How can you kill or immobilize the bees?

Dr. Eric Mussen, a California extension bee keeper, writes in his newsletter From the U.C. Apiaries, "The answer in many  cases, especially in areas of Africanized bees, is 'soap water.' Mix one cup of dish washing detergent in a gallon of water and apply to the swarm using any sprayer. He says it is just as effective as using a flame thrower.

cases, especially in areas of Africanized bees, is 'soap water.' Mix one cup of dish washing detergent in a gallon of water and apply to the swarm using any sprayer. He says it is just as effective as using a flame thrower.

Dr. Mussen believes this works because detergents are "wetting agents." This means that water sticks to every surface of the bee instead of running off. The bees are unable to fly with wet wings [and perhaps heavier body weight when wet?]. The spiracles, or breathing holes, which normally are able to repel water, are entered by the "wetter" water, suffocating the bee.

Do not use it near a hive where it might get on the comb, if you want the hive to return to normal activity. [The above is based on an article in Apis, the state of Florida beekeepers' newsletter.]