- What About Rhizobia Inoculants?

- How Adequate is Chicken Manure Tea as a Fertilizer?

- How to Make Fish Emulsion Fertilizer

- Pigeon Pea and Chickpea Release Phosphates

- Plant Tissue Nutrient Tests Available at Ohio State University

- "Feeding and Balancing the Soil" Course

- International Ag-Sieve

"WHAT ABOUT RHIZOBIA INOCULANTS? I don't recall any mention of them in the 'Seeds Available from ECHO' listing. Isn't it likely that many of the legume seeds will need rather specific rhizobia inoculants at planting time?" wrote Bob Tillotson in Thailand. "Does the seed [velvet bean] need to be inoculated to fix nitrogen or will it naturally do it on its own?" from Jim Triplett in Guam. Similar questions regarding legume inoculation come up often. The following attempt to answer these questions is based on an article by Dr. Paul Singleton with NifTAL which was sent to us by one of our readers, Brian Hilton. The article, "Enhancing Farmer Income Through Inoculation of Legumes with Rhizobia: A Cost Effective Biotechnology for Small Farmers," addresses a series of questions. We will summarize these and add a few others.

What are rhizobia and what do they do? Rhizobia is a genus of soil bacteria that infect the roots of legumes and can fix (make available to the plant) atmospheric nitrogen. Unlike disease-causing bacteria, rhizobia enter into a symbiotic relationship with the plant. The legume provides the bacteria with energy and the bacteria provides the legume with nitrogen in a form it can use.

Does one rhizobium work with every legume? No, rhizobia are selective and grouped according to which legume species they will colonize. The rhizobia of some species, e.g. leucaena, are very specific. Others cross-inoculate many species. For example the "cowpea family of inoculant" will inoculate Acacia albida, Cajanus cajan (pigeon pea), Desmodium spp., Lespedeza spp., Mucuna spp. (velvet bean). Some species, such as peanut, called "promiscuous," can be inoculated with any of a number of rhizobia. Often one rhizobium strain will provide some biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) but will be less effective than another. Unless some strain of inoculant suited to the legume species you are growing is present in the soil, no BNF will take place.

Which of my crops are most likely to respond to inoculation? Responses are likely from species whose rhizobia are quite specialized such as soybeans and leucaena. Areas with a distinct long dry season of 6-8 months are also likely to respond due to existing rhizobia populations dropping off more quickly under these  conditions.

conditions.

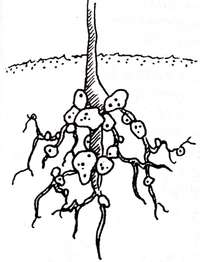

How do I know if I need to inoculate my plant? Rhizobia live in nodules on the roots and can be easily seen. Well nodulated legumes will have nodules on the tap root. (Dig the plant and remove the soil carefully or the nodules will fall off.) Not all nodules are effective, however. Cut several nodules in half. Nodules that are effectively fixing nitrogen will usually be red or pink inside.

How are rhizobia introduced? Most commonly legume seeds are coated with the appropriate inoculant just prior to planting. A sugar or gum arabic "sticker" is used to attach the powdery inoculant to the seed. If healthy, nodulating plants of the same species are already growing in the area the proper rhizobia should already be available and need not be purchased. Just add about 5 g of soil from such a plot to each hole as seeds are planted.

Can I maintain my own inoculant? Yes. After a successful crop, soil will always retain some inoculum until the next season. Replanting the same species in the same soil year round will serve to increase inoculum for that crop. But, this practice may also increase the occurrence of some diseases.

Why doesn't ECHO carry inoculant for the legume seeds it distributes? This would seem to be the wise thing to do. However, it is challenging enough to preserve and monitor the viability of our stored seeds. Viability of inoculum is even more difficult to monitor and maintain which is why we leave this enterprise to those set up to do the job well.

How much rhizobium is needed to inoculate a seed? It takes about 100 grams of inoculant to sufficiently treat one pound of leucaena seeds. A hectare of soybeans requires 286 grams of inoculant. Quality is more important than quantity. The best inoculant contains a billion rhizobia per gram, but it doesn't take long for quality to drop. This is why inoculation is done just prior to planting. Since you can't tell if inoculant is good or bad by looking at it, care should be taken to purchase from a good source and handle it properly. Inoculant should be protected from heat, light and desiccation and used as soon as possible. If a cool storage area is not available, a pot buried in a shady area is a good option. If transportation is required, a container covered with a damp cloth works well.

Where can rhizobia be obtained? Many countries manufacture inoculants for a number of crops. Contact your local agricultural extension agency or national department of agriculture to see if they have the inoculant you are looking for. If it needs to be imported, probably the best source for trees would be AgroForester Tropical Seeds (P.O. Box 428, Holualoa, HI 96725, USA; phone 808/326-4670; fax 808/324-4129; e-mail agroforester@igc.org). Liphatech Company (3101 West Custer Avenue, Milwaukee, WI 53209, USA; phone 800/558-1003 or 414/351-1476; fax 414/351-1847) has inoculant of many species, including GMCCs which are not trees. ECHO has a running list of sources we have come across to date; let us know if you cannot find a source. More information on this topic can be obtained by contacting the University of Hawaii NifTAL Center (Nitrogen fixation by Tropical Agricultural Legumes; 1000 Holomua Road, Paia, HI 96779, USA; phone 808/579-9568; fax 808/579-8516; e-mail NifTAL@.hawaii.edu). Other possibilities include the international agricultural research center nearest you (e.g. CATIE, CIAT, ICRISAT, IITA, IRRI, etc.), UNESCO (Microbial Resource Centre, Karolinska Institute, 10401 Stockholm, SWEDEN), or the BNF Resource Centre (Soil Microbiology Research Group, Rhizobium Building, Soil Science Division, Department of Agriculture, Bangkok 10900, THAILAND; fax 662-5614768).

Some concluding remarks: Each situation is different. If farmers can obtain inoculant quickly and reasonably it can be a low-cost input with high returns. If planting something like soybeans for the first time in an area, special efforts should be made to obtain proper inoculant. Legumes will grow without rhizobia, they will just require mineral sources of nitrogen like other plants. Even with proper inoculation, factors like low phosphorous, low pH and insect damage will limit yield. It should also be noted that it can take up to 20 days for biological nitrogen fixation to get going, so an application of nitrogen just after germination can help even if rhizobia are present.

HOW ADEQUATE IS CHICKEN MANURE TEA AS A FERTILIZER? One aspect of ECHO's ministry is behind the scenes for most of our readers. We help college professors and students in the sciences identify research projects that would be of benefit to the small farmer. Several ideas that could be done at an undergraduate level are written up in what we call Academic Opportunity Sheets. Nathan Duddles, while an undergraduate at California Polytechnic University, did an outstanding job answering the above question. I should think his 100-page report is of master's thesis quality.

He placed fresh chicken manure in a burlap bag, added a rock to make sure it did not float, and set it in water in a 35 gallon garbage can. If you were making such a tea, how long would you let it set to get out most of the nutrients? Nathan measured nitrogen in the "tea" each week and found that with 20 pounds of manure the maximum was nearly reached after only 1 week. It took 3 weeks with 35 and 50 pounds. However, the concentration apparently became so high that bacteria stopped working because he got even less nitrogen with 50 pounds than with 35 pounds.

How does the tea compare to an ideal hydroponic solution? He measured several nutrients in the tea made from 20 pounds after 4 weeks. After diluting it to a fourth its original concentration he compared it to one such standard hydroponic solution. The tea concentrations followed by the standard are: total nitrogen (219; 175), nitrate (4; 145), ammonium (215; 30), phosphorous (54; 65), potassium (295; 400), calcium (6; 197), sodium (62; 0), magnesium (0; 2), iron (0; 2), manganese (0; 0.5), copper (0; 0.03), zinc (0.05; 0.05). The major nutrients and zinc are adequate. Only calcium and tiny amounts of iron, manganese and copper would need to come from another source. Unless you are growing hydroponically where all nutrients must come from the tea, these should be available from the soil or compost. He suggests that lowering the pH from 7.3 to near 6 might provide some of these, or some might come from dilute sea water.

Total nitrogen was ideal, though it would preferably be in the nitrate rather than ammonium form. However, the tomatoes grown with the tea or a hydroponic solution (somewhat different and less ideal than the one above unfortunately) grew only marginally better with the chemical preparation.

Tomatoes were grown in wood chips to see how the tea would work with our rooftop gardens and in sand or sawdust for comparison. Growth in wood chips was superior in every case, apparently because the other two were so wet that roots could not get enough air. He analyzed the concentrations of nutrients present in plant tissues and found that the only significant difference was that plants grown with manure had more sodium. The micronutrients must have come from the growing medium. We have a Technical Note on this subject for those interested in more details.

HOW TO MAKE A FISH EMULSION FERTILIZER. We had been asked this question but I never knew the answer until Organic Gardening answered it in their February 1990 issue. It does not make me want to go to my suburban home and try it, but I could see its use on the small farm.

"Place fish scraps in a large container and add water. Cover the top securely with a cloth plus a wire screen to keep out animals and insects. Put the container in a sunny location to ferment for 8 to 12 weeks. You can add a small amount of citrus oil or other scent to mask some of the odor, but be sure to keep the container where your neighbors won't complain. Try to avoid spilling any fish scraps or fishy water on the ground, where they will attract animals. When finished, a layer of mineral-rich oil will float on the water, and fish scales will have sunk to the bottom. Skim off the oil and store in a tight-fitting container. To use, dilute 1 cup of oil with 5 gallons of water. Your homemade fish emulsion will be rich in nitrogen, phosphorous and many trace elements, but generally low in calcium."

PIGEON PEA AND CHICKPEA RELEASE PHOSPHATES. (Based on an article in International Agricultural Development, April 1992.) We all know that legumes such as these two plants add nitrogen to the soil. Now scientists at ICRISAT in India have shown that they make available more phosphates. They do not add phosphate to the soil, but rather break up phosphate compounds in such a manner that phosphate that was already present but unusable by plants is now available. If you work where phosphate is one of the most limiting nutrients (a common situation in tropical soils), you might want to work these crops into your rotation.

PIGEON PEA AND CHICKPEA RELEASE PHOSPHATES. (Based on an article in International Agricultural Development, April 1992.) We all know that legumes such as these two plants add nitrogen to the soil. Now scientists at ICRISAT in India have shown that they make available more phosphates. They do not add phosphate to the soil, but rather break up phosphate compounds in such a manner that phosphate that was already present but unusable by plants is now available. If you work where phosphate is one of the most limiting nutrients (a common situation in tropical soils), you might want to work these crops into your rotation.

How do they work? Studies show that the roots of pigeon pea exude acids (piscidic acid) which release phosphorous when it is bound up with iron. Chick peas release another acid (mallic acid) from both roots and shoots. In calcareous soils (alkaline soils with high calcium content), this acid breaks up insoluble calcium phosphate. Normally this release would only occur if the pH of the soil were lowered.

Both plants "are deep rooted, so their ability to release more phosphates means that valuable nutrients are being brought up from the deeper soil layers. Residues from both crops are adding extra phosphates which will benefit the crops which follow in the rotation. It is possible that some varieties ... exude more acid than others. So this trait could be another characteristic for selection [by plant breeders]."

PLANT TISSUE NUTRIENT TESTS AVAILABLE AT OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY. This technique is more sophisticated than most of you will require, but readers do occasionally ask us where they can get leaves of a plant analyzed to see what nutrient is causing a certain symptom. "Are the leaves yellow for lack of nitrogen or iron?" The theory behind this technique is that the ideal place to look for a nutrient deficiency is in the plant itself, rather than the soil. For example, even though a soil test might show that a particular nutrient is present in the soil in adequate amounts, a deficiency of that nutrient could still be causing the deficiency symptoms if for some reason (e.g. high pH) the plant could not take it up. A foliar spray with that nutrient might solve the problem.

I read in a newsletter that the Ohio State University experiment station offers this service at a good price. I wrote asking how one could get soil or plant material into the States for analysis. Professor Maurice Watson said you need to obtain a customs permit number from them, then send samples to them directly for analysis. No doubt many other Land Grant Universities offer similar services.

The standard plant tissue analysis for nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, manganese, iron, copper, zinc and boron costs $12.00. The standard soil test for pH, lime deficit, available phosphorus, exchangeable potassium, calcium and magnesium, cation exchange capacity and percent base saturation costs $6.00. Many other tests are offered, such as organic matter, available minerals, and heavy metals. Write the Ohio State University; R.E.A.L.; Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center; Wooster, OH 44691; USA; phone 216/263-3760. Prices quoted were in effect April 1995. Be sure to write them for current prices, detailed instructions on how to take samples, how much to send, etc. before submitting any samples.

"FEEDING AND BALANCING THE SOIL" is a five-day short course taught by Neal Kinsey, author of Hands-On Agronomy, about $475 registration fee includes lunches. Offered annually (during July in 1995), at Little Creek Acres, a non-profit demonstration farm for sustainable agriculture. Other courses are offered from time to time. For information write Center for Living in Harmony, 13802 Little Creek Lane, Valley Center, CA 92082, USA; phone 619/749-9634; fax 619/749-0720.

INTERNATIONAL AG-SIEVE is "a sifting of news in regenerative agriculture." This publication changed format in 1995 to 4-page information sheets on specific topics in ecologically sound agriculture. Issue #1 was on vermicomposting (using worms to produce high-quality fertilizer); issue #2 discussed the benefits of soil-improving legumes. Each edition has basic information, contacts, and publications on the theme. Readers are encouraged to follow up specific questions with the professional references listed. An index of available issues is sent periodically to individuals on the mailing list, and readers select the issues they wish to receive (about $4/issue). They hope to publish 12 issues per year. Send your name, address, and a brief description of your work to International Ag-Sieve, Rodale Institute, 611 Siegfriedale Rd., Kutztown, PA 19530, USA; phone 610/683-1400; fax 610/683-8548.