Introduction

Inclusive development has become increasingly a priority for development organizations. This focus on inclusive development has led organizations to address the particular needs of persons with disabilities in specific development sectors. One area of growing attention is in inclusive water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programming. Since 2007, World Vision and the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation have partnered with the Collaboratory, an applied research and project-based learning center at Messiah College, to fund the Africa WASH and Disabilities Study (AWDS). The AWDS seeks to improve the access to and use of WASH facilities by persons with disabilities in communities targeted by World Vision and the West Africa Water Initiative (WAWI) in the countries of Mali, Niger and Ghana. One of the primary ways in which the AWDS seeks to address the needs of persons with disabilities is through the development of simple, low-cost, assistive WASH technologies.

As part of the AWDS, assistive technologies will be designed in each of the three target countries. The process is already underway in Mali. The technologies which have been designed thus far are based upon the needs and preferences of persons with disabilities in World Vision target communities in rural Mali. A survey and focus groups were conducted in the target communities to identify the priorities of persons with disabilities in regards to WASH. Feedback from the surveys and focus groups revealed that persons with disabilities faced significant constraints in the following three areas: • Access and use of hand-pumps • Transport and domestic use of water • Access and use of latrines

Two of the technology sets designed by persons with disabilities to facilitate access and use of latrines are presented in this paper: latrine chairs and a latrine hole locating system for persons with visual impairments. These technologies were developed and fabricated in a developing world context using only locally-available materials and construction techniques. It is hoped that these technologies may be useful to others working with persons with disabilities throughout the developing world.

Sanitation and Latrine Constraints

Results from the survey and focus groups brought to light the numerous difficulties faced by persons with disabilities in relation to sanitation and latrine use. In the targeted communities in Mali, more than 60 percent of rural households reported they do not have a latrine. Many persons who lack a latrine urinate in the drainage of the “bathing” area of the household, and most people go outside their homes to defecate (usually to the “bush” or adjacent crop fields). The lack of latrines in most households causes unique challenges for persons with disabilities. Those with mobility limitations are often faced with the need to regularly traverse significant distances. Many persons with disabilities choose to wait until after nightfall to relieve themselves, as they are not required to travel as far to find a place of concealment. However, this practice carries with it the risk of encountering poisonous snakes or scorpions, or incurring other types of bodily harm.

Thirty-five percent of the survey respondents reported the presence of a traditional latrine, with about five percent having some form of improved latrine. Among persons with disabilities who have access to a latrine, 85 percent indicated that they have to touch the latrine floor while accessing the latrine or to stabilize themselves. Only 14 percent of the respondents indicated using an assistive device to help them use the latrine.

Perhaps the most challenging issues related to latrine use are squatting and cleaning. Persons with lower-body limitations often have difficulty in one or more of the following actions: a) lowering themselves to a squatting position; b) maintaining a squatting position without the support of their hands; c) cleaning themselves after defecation; and d) raising themselves to a standing position when finished.

Latrine Chairs

In order to minimize the numerous challenges

noted in regards to latrine use, technologies designed to provide adequate seating and assist with personal cleaning were developed and tested. The main technologies developed were clay terra cotta latrine seats and metal and wooden latrine chairs.

Clay Terra Cotta Latrine Seats

Clay terra cotta latrine seats can provide a low-cost solution for persons with disabilities who lack sufficient lower-body strength to squat (see Figure 1). Many moderate-sized villages and towns in the target region have skilled, traditional potters who produce terra cotta containers for water transport and storage. AWDS representatives worked with a local potter to develop and test several prototypes for use with both traditional latrines and the sanplat (sanitation platform) system. These seats can be produced for the affordable price of approximately 400-1,500 cfa (West African franc) (.80₵ $3.00 USD) each.

The technology development process revealed that persons with disabilities had varying preferences for seat height based upon their individual impairment(s) and the size and type of latrine hole. However, site tests revealed that the standard height for these should remain within the 15-20 cm range. Circular seats for traditional latrines should have a diameter of about 25 cm, but this can vary depending on the size and shape of the traditional latrine. Terra cotta seats for the sanplat should be fabricated by simply following the dimensions of the latrine opening. The top rim should also have wide and well-rounded edges to provide greater comfort to the user.

There was a largely favorable response from persons with disabilities assigned these seats for testing over a period of six months. In addition to no longer having to sit directly on the latrine hole, the low-cost and ease of local fabrication was particularly appealing. The seats are weather resistant and can be left in the latrines year round.

Despite the benefits of the clay seats, field testing revealed several minor challenges. The seats are heavy and must be placed and removed with each use so that other family members can use the latrine. In some cases, another family member assisted in placing and removing the clay seat. Additionally, while personal cleaning is made somewhat easier and more hygienic than when seated directly on the hole, some individuals still struggled with this as it is still difficult to reach one’s buttocks with a cupped handful of water. The seats can be brittle and must be handled with some care to avoid breakage if dropped. In terms of comfort, some persons cited mild discomfort due to the hard nature of fired clay.

Metal Latrine Chairs

In order to provide an assistive device that was both more portable and more conducive to washing, AWDS representatives worked with local metalworkers and volunteers to design and test metal latrine chairs (see Figure 2). Several prototypes were developed and tested over a period of 18 months, with both male and female volunteers.

Field testing of the metal latrine chairs revealed numerous technical specifications that increase the chair’s overall functionality and comfort. For instance, the optimal height of the latrine chair should normally be about 20 cm. This height is based on user preferences and the need to keep the chair seat relatively close to the latrine opening to avoid possible soiling of the latrine surface. If there is an object the seat must fit over, or if the individual needs a higher position due to a physical limitation, then the seat can be positioned higher. Additionally, the specifications of the latrine seat can vary based upon user preferences. However, field testing revealed that the appropriate seat width should range from 15-25 cm, with most persons usually preferring a width of 20-25 cm. The length of the seat portion of the chair should be about 30 cm.

It should also be noted that the metal chair designs are open at one end. This opening is necessary to facilitate hand access for cleaning and rinsing after defecation. The seat opening does not need to be larger than the maximum width of the seat. Early chair prototypes were built with circular (or enclosed) seating and did not include these openings. User feedback quickly indicated that this design impeded effective hand access and cleaning, and the future designs were adapted accordingly.

Field tests also revealed that the total chair width should normally not exceed 50 cm, as greater width can make access difficult when passing through the entrance ways of many latrines. The depth of most chairs (i.e., the distance from the front to the back of the chair) will need to be slightly more than the length of the seat portion of the chair. Typical depths may range from 35-45 cm. By limiting the width of the chair, persons with disabilities can more easily transport the chair between their homes and the latrine. In addition to the dimensions of the chair, consideration must also be given to stability. Low-placed braces between chair legs can serve to enhance seat stability and prevent chair legs from sinking in the soil surface.

The handles on each side of the latrine seat are used primarily for proper placement of the seat and for lowering and raising oneself from the seat. The height of the side handles will therefore depend on the strength and preferences of the user. For most users, the handles should extend approximately twice the height of the seat (usually 40-45 cm). However, some persons with disabilities and elderly persons can benefit from higher side handles which will allow them to use the chair as a walking aid. When used in this manner, the individual can leave their assistive device (tricycle, crutches, etc.) outside the latrine and enter without becoming soiled from the latrine or bathing area floor. Chair handles that will be used to assist with walking should be about 65-70 cm in height.

The metal chairs can be fabricated by local metalworkers, and they are comfortable, portable, strong and degrade little when exposed to water and sun. However, their primary disadvantage is their cost, which generally ranges from 8,000-10,000 cfa ($16.00$18.00 USD), depending on the type of design and the amount of metal and welding involved. Without some form of assistance, this cost is prohibitive for most persons with disabilities in rural communities of Mali.

Wooden Latrine Chairs

The AWDS also examined lower-cost wooden latrine chair options. Various models were developed, tested and improved over a twoyear period. The same guidelines mentioned for metal chairs also generally apply to the development of the wooden version. However, these chairs can be produced by local artisans for a much lower price of approximately 1,000-2,500 cfa ($2.00-$5.00 USD). A standard model which can be used by the majority of persons with disabilities with lower-body limitations was developed (see Figure 3). Field tests revealed the ideal dimensions of the chair as follows: width approximately 51 cm, length approximately 42 cm and height approximately 40 cm. Refer to Figure 4 for the recommended dimensions for the wooden latrine chair seat.

Discomfort caused by the thin gauge metal wire used to bind the chair together can be easily overcome if grooves are first cut in the wood before binding takes place. When the seat is attached to the chair frame, the wire binding can then be embedded in the pre-cut grooves to provide a smoother seat surface. The cut ends of the wood sections which will come in contact with the individual when seated should also be rounded to create smoother and more comfortable edges.

In addition to being low-cost, the wooden model is lightweight, easily portable and weather resistant. The wooden chairs should last for several years without needing replacement. However, repeated use and long-term exposure to rain and sun can reduce the strength of wire binding over time. Tightening or replacement of the wire binding may need to be done every two to three years if the chair is typically stored outside in the open latrine area.

Special Challenges for Persons with Visual

Impairments

For persons with visual impairments, traversing the courtyard and the latrine structure can be difficult, much as it is for persons with other forms of disability. Most challenging for persons with visual impairments, however, is locating the latrine hole and positioning oneself accurately over the hole in a squatting position. In both Mali and Niger, it was noted that most persons with significant visual impairments simply use their unprotected hands to locate the hole.

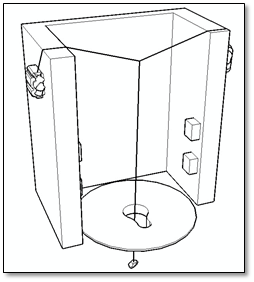

Latrine Hole Locating System

A simple, low-cost method for assisting persons with visual impairments was tested in Mali. This involves the use of string weighted with stones (see Figure 5). A string is suspended across the walls adjacent to the sanplat using stones attached to both ends. A second string is attached at the center of the cross string, directly above the latrine hole. This vertical string is then weighted at its low end with another stone and is lowered into the latrine hole some 40-50 cm below the surface of the sanplat. This vertical string is permanently fixed in this position and should not be removed (as the lower end will be soiled) except for repair.

The person with visual impairments can locate this string and the general location of the latrine hole with an outstretched hand. When descending to a squatting position he can then keep one hand on the string for accurate body positioning over the hole. As he squats, the string under tension will give way to the side while he remains in the squatting position. This system was tested for 12 months and was found to be easily mastered by adults with visual impairments. One concern was that other household members would remove the string or that curious children in the household would play with it or otherwise disturb the weighted string system. However, after one year of testing in a household that included a father with visual impairments with a spouse and several young children (to whom the string’s purpose had been explained), not a single incidence of disturbance was reported. To reduce the frequency of repair, the string material should ideally be resistant to deterioration from wetting and from ultra-violet rays from the sun. For testing, a low cost, UV resistant cord was used.

Conclusion

In rural West Africa, significant challenges impede the access to and use of WASH facilities by persons with disabilities. In order to confront these challenges, the AWDS designed and tested low-cost assistive technologies in target communities in Mali. The AWDS spent several years working with persons with disabilities to design and test assistive technology prototypes. The two technology sets presented in this paper represent the ideal technical guidelines as made clear by persons with disabilities in the target communities. It is hoped that the specifications presented in this paper will be used to assist others working with persons with disabilities in the developing world

Cite as:

Kamban, N. and R. Norman 2012. Developing Low-Cost Assistive Technologies for Persons with Disabilities. ECHO Development Notes no. 117