Figure 1. Moringa leaf powder. Source: Tim Motis

What is moringa leaf powder?

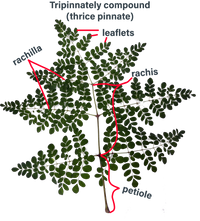

Figure 2. Diagram illustrating parts of a moringa leaf. Source: Tim Motis and Stacy Swartz

Moringa oleifera is a fast-growing, tropical tree known for its nutritious leaves, eaten raw, cooked, or dried and ground into powder (Figure 1). Here we’ll focus on moringa leaf 1 powder, which is easy to store and add to foods. The ability to store moringa powder allows people to benefit from moringa during times such as the dry season when moringa trees are less productive. Added in modest amounts, moringa powder does not appreciably alter the taste of the food and is an excellent way to boost the nutrition of local dishes. Questions arise about how best to process the leaves for quality moringa powder. This article expands on an earlier ECHO publication (Doerr and Cameron, 2005), summarizing factors before and during drying that influence the quality of moringa leaf powder. It also discusses drying methods and practical ways to optimize post-harvest processing for improved nutritional quality.

How are moringa leaves prepared for drying?

Moringa leaves need to be dried before converting them into powder. Wearing gloves while handling leaves is good practice for producing clean moringa powder. Sanitation is especially important if you are producing moringa powder for others. If you are producing moringa powder for a business, be aware of required practices and standards for acceptable quality. Table 1 covers the basic steps to harvest, wash, and prepare moringa leaves for drying.

Here [http://edn.link/9eh4c4] is a brief video illustrating how to harvest a moringa leaf from a branch, remove leaflets, and place leaflets on a drying screen.

The rest of this article will focus on drying factors and methods.

What factors should I be aware of in drying moringa leaves?

Air circulation

Air circulation facilitates drying and prevents moist conditions conducive to mold and rotting. Ensure adequate air circulation by spreading the leaves out thinly on your drying surface. Inner layers of thick piles of leaves will stay moist too long. Place leaves in mesh bags/cloth or on screened drying shelves/racks to allow air exposure on all sides. Fans increase air circulation and are often incorporated into cabinet dryers. Gentle air movement is best, to prevent leaves from blowing around in the dryer.

Temperature

The higher the drying temperature, the faster your leaves will dry. Faster drying minimizes the likelihood of mold, but high temperatures reduce vitamin content (Alakali et al., 2015 ) and other health-promoting compounds like quercetin (Ademilui et al., 2018). ElGamal et al. (2023) stated that optimal drying temperatures for retaining vitamin C in vegetables range from 35 to 60°C. Minerals like calcium and iron were well retained at these temperatures in a study in Nigeria by Alakali et al. (2015).

Light

Working with cowpea leaves, researchers in Uganda found that drying in the sun reduced vitamins A and C by 58% and 84%, respectively (Ndawula et al., 2004). They attributed the losses to the effects of ultraviolet radiation.

Time

Dry leaves until they become crisp and brittle. Brittle leaflets should break apart easily. Soft leaflets that bend without easily breaking likely have too much moisture. Adjust air circulation and temperature to dry moringa leaves fast enough to prevent mold while retaining vitamins.

Humidity

Figure 3. A screened drying rack suspended near the underside of a metal roof. Source: Tim Motis

High humidity increases the time to dry moringa leaves. The longer the leaves remain moist, the greater the risk of mold and rotting. Under high humidity, it is important to have good air circulation and sufficient heat. If you are drying moringa leaves during the rainy season without electricity you may want to:

- Dry the leaves on screens or in mesh bags. Doing so, and spreading the leaves thinly, exposes more leaf surfaces to the air.

- Hang the leaves near the roof 2in a well-ventilated room (Figure 3).

- Mix/move the leaves around a few times during the drying process to make sure all the leaves are exposed to air.

Contaminants

Dry leaves in ways that minimize contamination of dust, animal droppings, and debris. This is most likely to be an issue with open-air drying in the sun or shade.

What are some methods of drying moringa leaves?

Options for drying moringa leaves include shade-drying, drying in direct sunlight, solar drying, and drying in an oven or cabinet equipped with a heat source and fan(s). An ideal drying method will optimize factors like air movement, temperature, and light to dry moringa leaves with minimal loss of vitamins. Your drying method also needs to be practical. A drying cabinet with a heat source and fan provides high-level control of temperature and air circulation; however, it requires electricity. Shade-drying probably retains more nutrients than sun-drying, but there is the risk of mold under high ambient humidity. Information for choosing and optimizing a drying method is summarized in table 2.

| Method | Strengths | Drawbacks | Optimization tips* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | Simple Low cost |

Risk of vitamin loss due to high temperatures and ultraviolet light Exposure to contaminants Slow drying on cloudy days |

Cover leaves with porous cloth to reduce ultraviolet light and protect the leaves from contaminants like dust. May need a barrier around the drying area if animals are present. Bring leaves indoors at night if cooler night-time temperatures are likely to cause condensation. |

| Shade | Simple Low cost High vitamin retention |

Slow drying time and risk of mold under humid conditions Exposure to contaminants Rehydration of leaves not dried sufficiently during the day and left out at night |

When drying indoors, place the leaves in air heated by the roof. May need a barrier around the drying area if animals are present. |

| Solar | Many design options No moving parts required |

Materials and construction cost Risk of vitamin loss if temperatures get too high and leaves exposed to ultraviolet light |

Maximize vitamin retention by using plastic that blocks ultraviolet light or by using a design in which solar-heated air rises into an enclosed drying space shielded from the sun (Figure 4). |

| Oven or cabinet | Ability to control temperature and air movement Can dry leaves on cloudy and/or rainy days |

Complexity and cost of heat source, thermostat, and/or fan(s) Vitamin loss to heat if temperature is not controlled well |

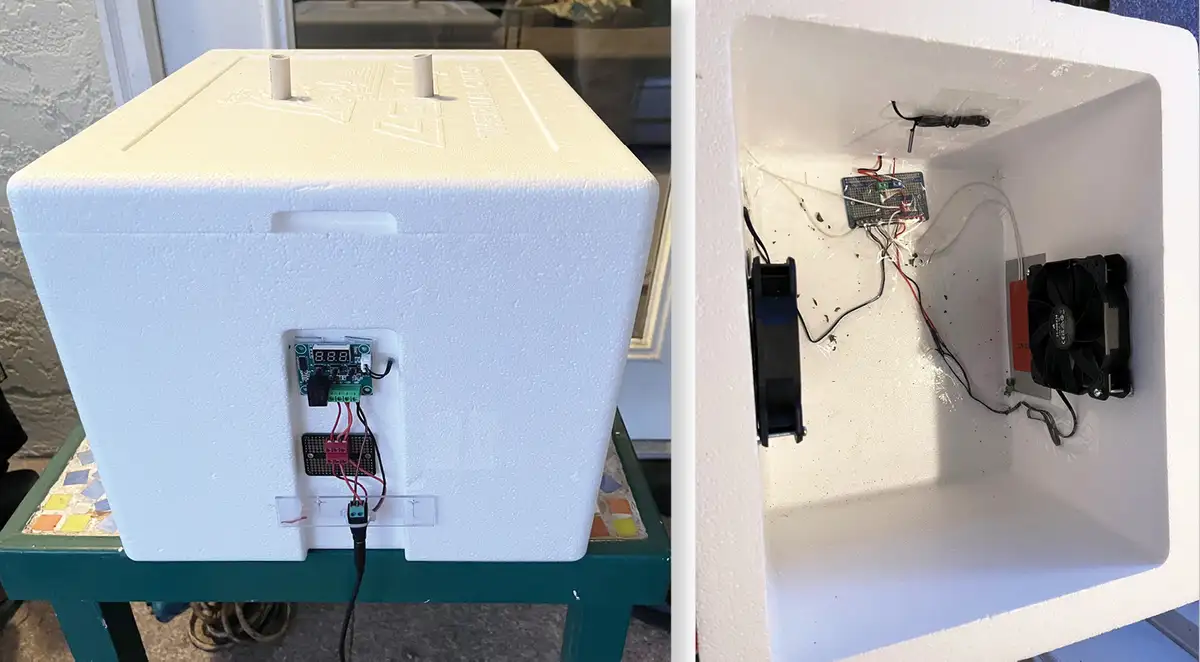

A low voltage system may be sufficient to dry leaves in a small box for household use.** If using a household oven, monitor the temperature closely. |

| *These are in addition to practices that apply to all drying methods, like placing leaves on screens or cloth and spreading the leaves out thinly on drying surfaces. | |||

| **A small drying box can be made with inexpensive materials such as 5- or 12-volt mini heating pads, a temperature controller, and computer fans (Figure 5). Experiment with holes added for intake (behind the fans) and venting (at the top) of air. | |||

Figure 4. A solar dryer used at ECHO in Tanzania. Sunlight heats the plastic surface of the heating box (bottom left). Heat then rises up into the drying chamber with screened racks (right). In this way, the leaf biomass is not exposed to ultraviolet light. Source: Stacy Swartz.

Figure 5. A temperature-controlled moringa dryer made with a styrofoam cooler (top), equipped on the inside (bottom) with 12-volt computer fans and mini heat pads. Source: Tim Motis.

What if I cannot achieve ideal drying conditions?

Assess unacceptable versus tolerable losses in quality

Rotting, moldy leaves pose an obvious health risk if consumed. This would be an example of unacceptable quality. Other examples would be leaves contaminated or burned (because of overheating) during the drying process.

It would be reasonable, though, to accept the risk of some vitamin loss in using heat to dry the leaves before they become moldy. Even with some reductions in vitamins or antioxidants, moringa leaf powder will still have nutritional benefits. In promoting or marketing moringa leaf powder, avoid overstating its nutritional composition. Reports by those who have studied the effect of drying approaches on moringa powder (e.g., Ademiluyi et al., 2018 and Ahmed and Langthasa, 2022 ) are useful in gaining a sense of what nutritional values to expect for the method you use. Additionally, an ECHO Research Note by Witt (2020) presents nutritional values for a realistic serving size (5 g) of moringa powder.

Learn the nutritional tradeoffs of drying options

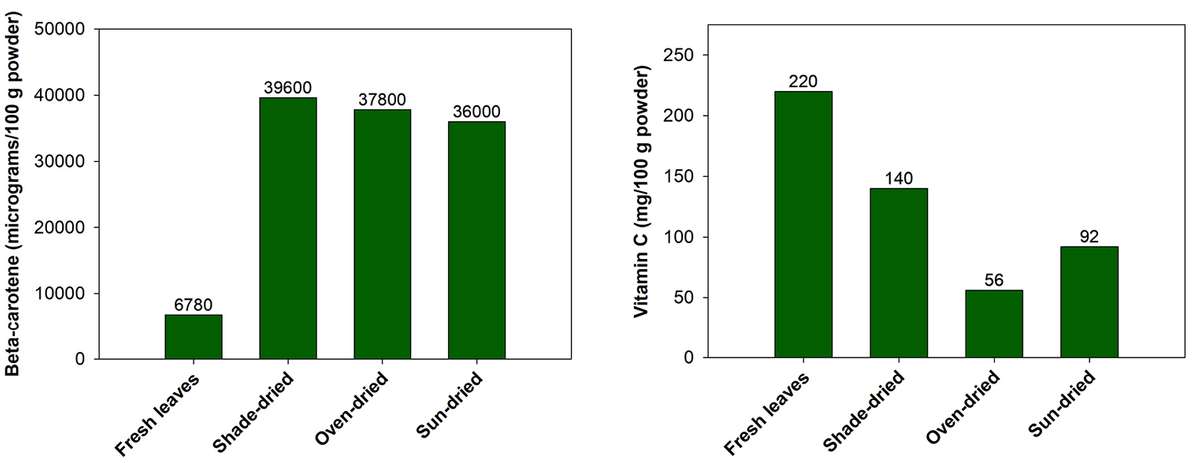

This is illustrated by a study in India by Joshi and Mehta (2010). The researchers compared established nutritional values of fresh moringa leaves with those of moringa leaves dried in the following ways:

- Shade drying, which they referred to as shadow drying. Leaves were placed indoors for 6 days on cotton sheets in a well-ventilated space, relying on natural air movement.

- Oven drying, with leaves on trays in a forced-air dehydrator at 60°C for 4 hours.

- Sun drying of leaves placed on cotton sheets and protected from dust and insects by covering with cheesecloth. To avoid rehydration of leaves at night the leaves were brought indoors each night for 4 days.

Figure 6. Effect of drying method on concentration of vitamins A (beta-carotene) and C. Adapted from: Joshi and Mehta (2010).

In their experiment, leaves were dried until they became brittle. Hence, the differences in drying time between methods. Although temperatures were not given for the shade and oven drying treatments, their findings shown in figure 5 are still instructive. Vitamins A and C were best retained by shade drying.

Minerals and protein varied little between methods. With respect to vitamins, the biggest losses compared to shade drying were those of vitamin A with sun drying (9% loss) and vitamin C with oven drying (60% loss). Even with a 60% loss of vitamin C with oven drying, a 5-g serving of the amount left would provide 19% of the 15-g recommended daily intake for a 1- to 3-year-old child.3

The nutrition of moringa leaves can also vary. Other researchers in India found that sun- and cabinet (shade)-dried moringa leaf powder contained 155 and 135 mg of vitamin C per 100 g of powder, respectively (Ahmed and Langthasa, 2022). In their study, cabinet-drying at 60°C reduced vitamin C by 25% compared to shade drying, quite a bit less than the 60% reduction found by Joshi and Mehta (2010).

Note in figure 5 that drying increased vitamin A while reducing vitamin C. Drying typically concentrates nutrients because it removes moisture in plant material leaves. The fact that drying decreased vitamin C suggests it is more sensitive to heat than vitamin A. ElGamel et al. (2023) mention that vitamin C is more susceptible to heat loss than other vitamins, so if your drying procedure retains vitamin C, other vitamins are probably retained as well. Knowing that vitamin C may be reduced by drying, you could also plan for other sources of vitamins in addition to moringa powder (e.g., fresh moringa leaves and leaves from other leafy greens such as chaya (Cnidoscolus aconitifolius).

Look for ways to work within limitations

Table 1 mentions examples such as coverings to protect the leaves from ultraviolet light for sun and solar drying. Nichols (2008) shared with ECHO a method they used in Burkina Faso, in which leaves are placed on woven plastic mats under pieces of corrugated metal roofing supported by boards (a link to their article is in the References section).

One approach for which there is little information available is the use of desiccant for drying moringa leaves. This concept was explored by Dodson (2012) as part of an undergraduate thesis project. Her work demonstrated the potential of desiccants (e.g., montmorillonite clay, silica gel, and zeolite) to reduce 90% of the moisture in moringa leaves in an enclosed space, without fans or a heat source. More experimentation could be done to find out how much desiccant is required to dry a given quantity of leaves. A desiccant approach could be practical for household use. Please let us know if you would like to experiment further with this or related adaptations and approaches (email publishing@echonet.org).

A word about shelf life

A general guideline for the storage life of moringa is 6 months, since nutrients in moringa powder decline over time (Adejumo and Dan, 2018). Maximize the storage life of your moringa powder by keeping it cool (room temperature or cooler), dry (in airtight containers that exclude humidity, and dark (light causes the powder to fade). Do not consume moringa powder that is molding or smells rotten.

Final thoughts

A good overall indicator of the quality of moringa powder is its color. It should be bright green. Greenness indicates that the harvested moringa trees were healthy, without nutrient deficiencies that lead to yellowing and discoloration. Reduced greenness is also linked to the degradation of chlorophyll caused by high-temperature drying (Ali et al., 2014). Discoloration can also be caused by decomposition/rotting that happens when the leaves stay moist too long.

Aim for a drying method that farmers and gardeners can readily implement with available materials. Look for low-temperature approaches to dry the leaves. Though drying may reduce some nutritional attributes of moringa leaves, moringa leaf powder still offers significant nutritional benefits. Consuming a mix of fresh moringa leaves and moringa leaf powder helps ensure that you get the maximum nutritional value from moringa. Finally, make moringa powder in quantities that can be consumed before it expires.

References

Adejumo, B.A. and E.J. Dan. 2018. Nutritional composition of packaged Moringa oleifera leaves powder in storage. Annals of Food Science and Technology 19(2):225-231.

Ademiluyi, A.O., O.H. Aladeselu, G. Oboh, and A.A. Boligon. 2018. Drying alters the phenolic constituents, antioxidant properties, α-amylase, and α-glucosidase inhibitory properties of moringa (Moringa oleifera) leaf. Food Science and Nutrition 6:2123-2133

Ahmed, S. and S. Langthasa. 2022. Effect of dehydration methods on quality parameters of drumstick (Moringa oleifera Lam.) leaf powder. Journal of Horticultural Sciences 17(1):137-146

Alakali, J.S., C.T. Kucha, and I.A. Rabiu. 2015. Effect of drying temperature on the nutritional quality of Moringa oleifera leaves. African Journal of Food Science 9(7):395-399

Ali, M.A., Y.A. Yusof, N.L. Chin, M.N. Ibrahim, and S.M.A. Basra. 2014. Drying kinetics and colour analysis of Moringa oleifera leaves. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 2:394-400

Anjorin, T.S., P. Ikokoh and S. Okolo, 2010 Mineral composition of Moringa oleifera leaves, pods and seeds from two regions in Abuja, Nigeria. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 12: 431–434

Dodson, A.L. 2012. The viable desiccation of Moringa oleifera in high humidity environments. A thesis in partial fulfillment of requirements for a baccalaureate degree. The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College. https://honors.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/1307

Doerr, B. and L. Cameron. 2005. Moringa leaf powder. ECHO Technical Note no. 51

ElGamal, R., C. Song, A.M. Rayan, C. Liu, S. Al-Rejaie, and G. ElMasry. 2023. Thermal degradation of bioactive compounds during drying process of horticultural and agronomic products: a comprehensive overview. Agronomy 13(6): 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13061580

National Institutes of Health. 2021. Vitamin C Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/#h2

Ndawula, J. J.D. Kabasa, and Y.B. Byaruhanga. 2004. Alterations in fruit and vegetable ß-carotene and vitamin C content caused by open-sun drying, visqueen-covered and polyethylene-covered solar-dryers. African Health Sciences 4(2):125-130

Nichols, J and A. Nichols. 2008. Drying moringa during the rainy season. ECHO Development Notes no.101:6. http://edn.link/edn101

Osumah, A.B. 2019. Effectiveness of Moringa oleifera L.AM. as soil amendment on growth and yield of Amaranthus caudatus L. and Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench. Dissertation, University of Ibadan. repository.pgcollegeui.com:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/507/EFFECTS%20OF%20MORINGA%20OLEIFERA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Sauveur, A.D.S. and M. Broin. 2010. Growing and processing moringa leaves. Moringa Association of Ghana (MAG), Accra, Ghana. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/63651

Witt, K. 2020. The nutrient content of Moringa oleifera leaves. ECHO Research Notes 1(1):1-18. http://edn.link/ern.