Integrating Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge for Sustainable Food Systems in Africa: The Plug-In Principle

link.springer.com/book/10.1007/9...8-3-031-85512-2

Review by Robert Walle

The success of the Millenium Development Goals depends on coordinated efforts by NGOs and governments working together. Development efforts with the best of inte ntions fail when implementers try to replace local knowledge and experience with external knowledge systems. This undermines resilience and sustainability. Even the World Bank recognized that programs fail when the people affected by them are not considered.

… no program will help small farmers if it is designed by those who have no knowledge of their problems and operated by those who have no interest in their future.

-Robert McNamara, President of The World Bank, 1975.

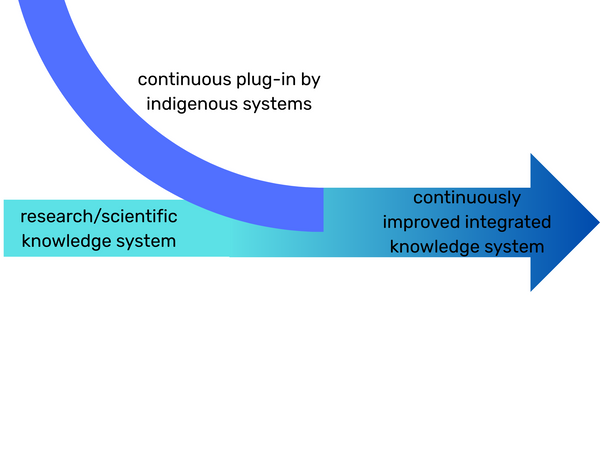

Figure 19. Simplified explanation of the plug-in principle. Source: Adapted from Dittoh et al., 2020.

Trying to replace local knowledge and experience has largely failed both in adoption and in agricultural production. This book on “Plug-in” principle (Figure 19) offers examples of solutions designed by the people affected by such decisions, recognizing the ingenuity of the community. Early on in the book, the authors show that many of the current practices to ease the effects of climate change, like conservation agriculture, regenerative agriculture, climate-smart agriculture, and agroecology, have roots in indigenous knowledge and small-scale agricultural systems. Examples from the book illustrate these diverse principles in action.

An irrigation study from Ghana shows how gender affects engagement with different practices. Women were more oriented to irrigating crops for household consumption rather than commercial sales, which limited women’s participation in areas like land tenure and finance. Plugging-in with attention to gender equity and respecting cultural norms helped the project co-develop improved irrigation practices, with women’s greater involvement.

Indigenous justice systems were also important for resolving conflicts between farmers and herdsmen in Ghana. The plug-in principle also applies to governance. The failure of colonial and independent governments in Kenya to understand the dynamics of Maasai pastoralism led to policies that degraded community rangelands. Revitalizing these indigenous justice and natural resource management systems is vital to sustainability.

A case study from South Africa shows the need for accurate translations of indigenous ecological knowledge. This requires continual community support and policy engagement among those who have abandoned traditional knowledge in favor of “modern practices,” particularly youth.

Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools can also “plug-in” to local food systems, supporting knowledge sharing and youth engagement. There is an interesting section about mobile phones improving existing communication. Plugging-in AI helped women’s entrepreneurship in the Sahel in the areas of business management and market access.

Building on what farmers already know helps create community ownership and fits into the existing local agroecology. This community ownership ensures that innovations proposed are culturally relevant and increases acceptance. Plugging-in first seeks to understand and respect local practices as a first principle before considering innovations. The book concludes with the need to change the research, training, and extension models that reflect a new “agri-culture”, a resilient, climate-smart agriculture that provides enough healthy food for all, is profitable, and recognizes gender differences and promotes equitable livelihoods.